Weekend Jaunt in Bogesundslandet's Nature Reserve

Carl and I took the opportunity of an unplanned, sunny June weekend and made for the Stockholm Archipelago. Because we didn’t want to spend the whole weekend traveling, we chose a nature reserve an hour’s bus ride from downtown. We got off the bus at the less popular northwestern end of Bogesundslandet’s Nature Reserve and planed to walk south to the water’s edge, find a waterside spot to pitch our tent, and spend the afternoon relaxing by the water. The walk started out less idyllic than we had hoped—almost immediately we were walking through clear cuts and the devastation continued for miles. As if it weren’t ironic enough that the state-driven logging was inside of the “nature reserve” boundaries, we found one of the boundary-marked trees in a stack of logs waiting to be hauled out.

Eventually we decided to hike toward the eastern part of the reserve—surely they hadn’t logged the popular areas around Bogesund’s Palace? Our intuition was correct and we were very relieved to find patches of intact forest. We hiked up to the top of Kvarnberget, or “Windmill Hill” and while the windmill is long gone, the view out to the water and toward Stockholm’s suburbs is still beautiful. We decided to set up camp on top of the hill and we had a lovely long evening enjoying the view.

It never gets truly dark at this time of year, so sleeping in the tent can be a challenge. This time, however, both Carl and I slept really well and we even managed to sleep in until almost nine o’clock the next morning!

After a lazy breakfast and some more reading with a view, we packed up our belongings and walked a whole mile to a beautiful flower-strewn meadow and decided that it was the perfect spot for lunch.

We picked some meadow flowers for tea and then continued on our way, this time walking for several miles in the (for Stockholm) blazing sun before jumping into the water for a swim. The water was brisk and refreshing, and we sat on up on a granite slab jutting out into the water for a couple of hours reading and drying off in the sun.

There is a ferry that traffics Bogesundslandet a couple time of day, and we had timed our walk for one boat, but it was so nice and pleasant in the sun that we decided to lounge on the granite slab until the next departure. It was a lovely lazy afternoon, and the boat back to the city was a fun way to travel—much more fun than the bus!

We were crushed at the beginning of our weekend jaunt to find the extensive logging in the nature reserve. I’m still seething. But we did manage to find some beautiful places to hang out in, and the unlogged parts of Bogesundslandet’s Nature Reserve definitely warrant more exploring.

SATURDAY, JUNE 10, 2017

Gotland, Sweden's Provence

Gotland is a large island out in the middle of the Baltic Sea about halfway between Sweden and Latvia. Carl and I spent four or five days on the island on one of our visits to Sweden before we moved here, and I instantly fell in love. But somehow, since we moved here, we hadn’t made it to the island until Carl’s parents bought a house on the island and a long-weekend visit became mandatory. My love affair with the island has been renewed and I’m already aching to go back.

Gotland is unique because while the island technically alternated being under Danish and Swedish control throughout medieval history, it basically operated as a free agent. The island is free of royal or noble estates and there is only one bishop’s estate on the island, but the bishop was allowed to visit only once every three years to prevent him from getting any control-seizing ideas. Instead of being controlled by royalty, the nobility, or the church, it was the powerful trading houses in the capitol city of Visby that were the main seats of power. Its strategic location in the middle of the Baltic made the island an ideal stop on trading routes between Russia, Sweden, Finland, Denmark, Germany, Poland, Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania. The city joined the Hanseatic League which made it even more prosperous.

|

| A few of Visby's medieval buildings. The building on the left is a storehouse. |

The entire island became incredibly, unprecedentedly wealthy in the early medieval period due to this unencumbered free trade and almost total lack of centralized taxation. It wasn’t just the city of Visby that became wealthy, but the entire island prospered as even “average” farmers participated in the trade networks. While most of Sweden was subsistence farming and dwelling in tiny log cabins with turf roofs, the residents of Gotland built large stone houses inspired by the latest medieval fashions from the continent.

|

| Hau and Grodda farms |

In addition to the stone farmhouses and barns, an amazing 92 stone churches were built on the island. Most of these churches don’t compete with the French cathedrals in size or splendor, but compared to the rest of early medieval Scandinavia, these churches were large and richly decorated, often with imported objects from the continent.

|

| Interior of Lärbro Church with pews painted in the 1700's and its medieval built-in sacrament cabinet. |

Gotland’s prosperity ended abruptly in the mid-1300’s. Trade routes began to skip Gotland but more importantly, the plague hit the island (and the rest of Sweden) killing somewhere between 1/3 to 2/3 of the population. Suddenly there simply wasn’t anyone around to do business, and those who were left had to support themselves with basic farming and fishing because there weren’t enough farmers left to keep townsfolk fed. Farms and entire villages were abandoned after the plague, and many areas weren’t repopulated until five hundred years later in the mid 1800’s.

This sudden change in economic circumstances had the beneficial side effect of preserving much of the island as it was in the 1300’s. Buildings were patched up and reused but no one could afford to tear old buildings down and build new ones. Church renovation projects halted and the half-finished products are still visible today with giant towers attached to strangely small naves. Small farms were never consolidated. Stone farmhouses and barns were never modernized.

|

| Fleringe Church. Many of the churches still have wooden roofs, and Fleringe's roof was getting re-tared the day we visited. |

As a sign of the unstable times after the plague struck the island, the only major, visible change that occurred during the later part of the middle ages was that the city of Visby’s walls were repeatedly reinforced and new, bigger towers were added in stages throughout the next 200-300 years. These walls and most of the towers are still intact today. Visby is Sweden’s only city with intact medieval walls today—all of the other cities outgrew their walls and tore them down in the growth process, but Visby never grew bigger than its medieval core. Not only are the walls intact, but the complex system of dry moats and outer banks are also still legible.

|

| The eastern, and northern stretches of city walls. The northern section meets the sea. |

To add insult to injury, the Reformation was another blow to the island’s economy and infrastructure. Wealthy monasteries and convents were closed, and many of Visby’s churches were allowed to fall into ruin.

|

| Ruins of St. Karin and St. Clemen's churches in Visby |

|

| The abandoned church at Elinghem. |

Gotland is Sweden’s example of La Dolce Vita. Even today, the pace of life is slower on the island. Organic farming is still a major occupation. Healthy, local, delicious food is a main focus of life. The historic cultural landscape is gorgeous, and scenic clusters of stone farmhouses dot the landscape. Small villages aren’t exactly lively but cottage industries and gourmet cafés thrive. The coastline is dramatic and beautiful with turquoise water and strange sea stacks. Gotland is home to several of Sweden’s most beloved artists, and there is a pleasantly creative vibe. Additionally, the island competes with Öland, both claiming that they receive the most hours of sunshine in Sweden. These days, prosperity reins once again, this time fueled by summer visitors to who stay at their summer cottages for weeks on end.

|

| Interior of Stenkyrka with paintings from the 1300's and 1400's. The church with its central column is fairly typical of Gotland's larger village churches--very awkward with the central pilar! |

During our visit, I began to think of Gotland as Sweden’s undiscovered Provence—it’s not a direct comparison (no vineyards or mountains!) but the island’s vibe and way of life and priorities feel similar.

Carl’s parents live in a modern house with a gorgeous sea view complete with gorgeous sunsets.

Aside from Carl’s mom’s gourmet dinners and clifftop sunset viewing, we didn’t actually spend much time at the house. Instead, we were out day tripping. The first day we all went up to Fårö, a smaller island off the north tip of Gotland. The atmosphere up there is more rugged and even more untouched by modern life, and the island definitely warrants much more exploring and time for checking out the incredible historic building stock (thatched roofs!).

|

| Some of Fårö's sea stacks. |

The other two days Carl and I borrowed his parent’s car and set off on our own. We spent one day motoring around the achingly scenic countryside and stopping at churches,

|

| Both the defensive tower to the left and Lärbro church were built during the 1100's on a wealthy farm. The church's tower was originally twice as high but it tumbled after a gale. |

|

| Cute cottages in Visby |

We were extremely lucky with four gorgeously sunny days in a row—not a common phenomenon in Sweden, but maybe it’s more common on sunny Gotland? The trip whet our appetites and we are eager to hop on the ferry for another trip!

|

| Ferry leaving the Stockholm Archipelago for Gotland. |

MONDAY, MAY 29, 2017

Celebrating Spring on Öland

Öland

is a large island off the eastern coast of southern Sweden. It is one

of Sweden’s widely recognized paradises where the sea, the relatively

high number of sunny days, and the beautiful cultural-historic landscape

conspire to make the island a coveted place for summer cottages. One of these coveted summer cottages has been in our friend Christian’s family since the 40’s, and he and Alison invited us down for a long weekend to share in their four-generation long tradition of escaping to the island. It was a lovely weekend where instead of rushing around sight-seeing, we sunk into the island rhythm of relaxation, sleeping in, walks, chatting, hanging out in the sun, and unpretentious but delicious meals.

Christian’s family’s cottage is at the edge of a cluster of summer cottages where the road ends and the beach paths through the trees and the dunes begin. It is a location made for walks on the beach where the dunes and the white sand and the sea oats and the turquoise water trick you into thinking you’re in the Caribbean, except that you need a down coat, wind breaker, hat, and scarf even in May. (Despite the chill, we still had to indulge in ice cream on the beach—we were celebrating spring after all!)

In the other direction, a lovely cultural landscape of farms comprised of small fields divided by stone walls, old farm houses and barns, and historic windmills invites walks down quiet and scenic country lanes.

The island has been inhabited for ages and is speckled with some of Sweden’s most fantastic prehistoric archeological remains including standing stones, stone fortresses, and fields of undulating grave mounds. On this trip, we stopped by a site with a cluster of very visible foundations of Viking-era long houses. Seeing the foundations, you can really understand why the buildings received the nickname “long house”—they are really quite impressively long!

We had a four-day weekend for Valborg, the traditional spring celebration. As it is my favorite Swedish holiday, I’ve written about Valborg several times before (see My favorite Swedish Holiday, Early Spring, Valborg 2013, and Summer has Arrived). This year, Alison, Carl and I drove across the island to the little town of Byxelkrok where a giant bonfire was lit on the quay by the sea. It was far larger than any of the fires we’ve seen in Stockholm, and I’ve always been so impressed with those! It was a beautiful and moving scene with the sky aflame in sunset colors, the undulating sea in the background, and the blazing bonfire in the foreground. The only thing missing was a mug of hot chocolate!

After a few restful days with our friends on the island, Carl and I took the bus to the mainland town of Kalmar. Kalmar is a cute little town on its own,

but its main draw is the fairytale Kalmar Castle which sits out in the bay and is cut off from land by a complex series of moats. A walled castle tower has been on the site since at least the 1100’s, and it was successively enlarged upon over the centuries. Several large additions throughout the 1500’s created the Renaissance-era castle that is visible today.

|

| Left: A moat separates the castle from the mainland. Right: The space in between the castle and the outer wall. Only the facade sticking up above the outer wall is ornamented. |

It’s not just the castle’s exterior that is impressive, but the interior courtyard is an atmospheric space

|

| (The painted stucco was an imaginative embellishment from the 1800's) |

The castle’s chapel also dates to the Renaissance but is a light and airy contrast to the dark, heavy interiors of the royal suite.

Kalmar castle is extra meaningful in Swedish history because it was here that in 1397 that Sweden, Denmark, and Norway were joined into a fateful union which lasted until 1523. Appropriately enough, that union was called the Kalmar Union. The castle’s signage is also still very proud of the fact that the castle was such a technologically advanced fortification that it was never taken by force and even survived a nine year (!) siege.

|

| Left: Unsuccessful canon balls embedded in the castle walls. |

A little bit of sight-seeing, a lot of chilling with good company, tasty meals, and beautiful scenery made for a lovely long weekend. Thank you Alison and Christian!

WEDNESDAY, MAY 17, 2017

Blessed by Reindeer

Carl

and I took advantage of the long weekend over Easter to go tour skiing

up in the mountains of Jämtland, a region along the mountainous border

with Norway exactly halfway up Sweden’s spine. We had been planning

this trip all winter, but after our snow-poor experience in Åre in

February (see "Skiing Sweden's 'Vail'" below), we decided it wise not to

book expensive plane or train tickets for Easter in mid-April.

Instead, we made a car rental reservation with the thought that we could

be flexible—we’d drive north if the snow lasted; otherwise we’d drive

south and check out one of Sweden’s many fairy-tale castles.As Easter approached, we checked the weather service’s snow coverage maps daily and watched as the snow receded, advanced, and receded again. Finally, a few days before the weekend, the snow looked promising-enough, so we called up to the mountain station and asked about the snow coverage. After receiving the answer that the snow was surprisingly good, we tried to make a reservation to rent touring skis. Unfortunately, the mountain station had already rented out all of the skis and boots in my size, so we had to re-plan a bit. Instead of starting at Storulvån, we found available rental skis at Vålådalen, just a bit to the east, so we decided to start there instead.

Driving out of Stockholm for the long weekend was amazingly painless, and the trip northward was unexpectedly easy considering that the main interstate highway going up Sweden’s coast is only one lane with an occasional passing lane that alternates between each direction. (!)

|

| Interstate highway, Sweden style |

The weather wasn’t great starting out, it was cloudy and a bit snowy, but as the afternoon progressed, the clouds cleared and by evening, we had sharply blue skies and beautiful mountain views. The first part of the trail crisscrossed through the forest and over a few streams, but it soon opened up onto a long series of bogs. Usually, the bogs would have been frozen solid at that time of year, but they were unfortunately ever-so-slightly thawed. Not thawed enough that we sunk in, but wet enough that our skis got icy and never recovered. After crossing the bogs, my skis continually gathered gigantic clumps of snow under them, so I wasn’t able to glide forward. Instead, I was walking on the skis, lifting up huge, heavy snowballs with every step. The ice clumps turned my skis into ridiculously tall and unstable platform shoes that were about a foot high and very risky for my ankles.

Needless to say, the middle part of the day’s journey was exhausting and frustrating. As soon as I took my skis off and scraped off the ice clumps, new clods began to form. Walking uphill was extra arduous, and by the time we reached tree line I was spent. Additionally, lifting the heavy skis wore out the muscle at the front of my thighs to the point that every step was painful. I wasn’t in a good mental place when we stopped for a snack about halfway to the cabin with only a couple of hours of daylight left. After our snack, I was freezing and my hands had suddenly crossed the line from cold to dangerously close to frostbite. I warmed up a bit and was determined to be positive, but then my ski stuck on a slight downhill and I fell on my face. I immediately burst into tears—I was so tired and exhausted and worried that we weren’t going to make it to the cabin before nightfall.

Carl helped me up and was hugging me when, in cosmic grace of good timing, a whole herd of at least 50 reindeer galloped across our path not 30 feet from us. The reindeer were so big, with such wide antlers, and with such skinny little legs. They sunk fairly deep into the snow but the snow didn’t deter them, they just gracefully pranced on. I had seen reindeer before, but never so many so close and in such a beautiful prancing gallop through the snow. It gave me an idea of how majestic and magical it must be to see the herds of caribou running in Alaska.

After the reindeer blessing, my skis stopped sticking, the views became more and more dramatic, and we reached the cabin at Vålåstugorna at least an hour before sundown.

The cabin at Vålåstugorna was much like the other STF cabins we stayed at on our ski touring trip last year (see “Arctic Adventure”) with bunkbeds separated into rooms of 4 and a big common kitchen and dining room with a wood stove for heat. The cabin was right above tree line, so we had beautiful views into the mountains and into the valley we’d be skiing through the next day. The valley looked very promising for big, dramatic mountain scenery.

|

| The cabin at Vålåstugorna |

Unfortunately, we woke up to a very foggy world. Since we were following a marked trail, we felt safe setting out on our 16 kilometer journey to the next cabin, but the views were not very exciting. Everything was the same color of milky white. It was very disorienting and I couldn’t distinguish uphill from downhill. I couldn’t even see Carl’s ski tracks directly in front of me. With no reference for up and down, I even started to feel a bit motion sick as I shuffled along.

Eventually the fog began to lift and we could see a bit more into the distance, but the fog lifted to reveal nothing but clouds that hung low below the peaks.

|

| Once the fog began to lift, we could make out a few features in the landscape. We stopped for a snack, using our windsack to stay warm and toasty while we sat in the sunless valley. |

|

| Lunch: lovely hot water and reindeer cheese from a squeeze tube on crackers. |

It was work getting to the top, but it really wasn’t too bad. And skiing down was so much fun! At first I was really hesitant because touring skis aren’t really known for their great turning capabilities, but the slope was gentle enough that wide, slow snow-plow turns worked well, even on our skinny touring skis. All too soon we reached our packs at the trail again.

We swished down from the pass to the cabins at Gåsen, which is at a high-alpine crossroads. There had only been 9 people staying at Vålåstugorna, and Carl and I even had our own bedroom, but Gåsen (“The Goose”) was pulsating with people. We ended up being very lucky in our timing because we were assigned the last two beds! The cabins are first-come-first-served, but no one is ever turned away. About 30 people that arrived after us were given mattresses to sleep on the floors of the various common rooms. Gåsen has beds for 51 people and there were 81 guests!

|

| The cabins at Gåsen |

The next morning, we left early and in the peaceful solitude of the trail, it was hard to imagine that the cabins had been so crowded the night before. We did see a few other people moving through the vast mountainous scenery during our 15 kilometer journey, but we felt very alone. The trail started out by climbing up to a high pass which was unfortunately socked in with clouds, but then it was basically 13 kilometers of downhill. Toward the top of the pass the trail was steep enough to warrant a few winding snowplow turns, but we mostly just glided along and let our skis carry us through the snowy landscape. It was a bit surreal—the vastness of the landscape, the feeling of being so exposed and alone, the effortless gliding on our skis.

|

| Down and down and down |

Toward the end of the day, the sun began to shine and the trail finally dipped below tree line again. Both Carl and I were sad—it felt like we were now officially starting the long trip home.

|

| Almost down to tree line. |

After being so disappointed to dip below tree line again, the cabin’s setting was a lovely surprise. It sits high on a bank above a small river, and over the river, there’s a magnificant view of dramatic mountains with almost two-thousand-meter drops from ridge to valley.

Carl and I spent the afternoon in the sun on the cabin’s porch reading, journaling, sketching, enjoying the view, and snoozing. Magnificent.

The next morning, we continued downhill back toward Vålådalen. The trail crossed quite a few bogs which were completely bare of snow by that point, so we had to carry our skis for long stretches. The bogs were frozen enough to walk on without getting our boots wet, but I imagine that they would have been impassible just a few days later. As we neared the car, we stopped for one last ski-touring lunch in beside a flowing river. All too soon we were back in civilization, returning the rental skis, and starting our eight hour drive back to Stockholm.

On the drive home, we got a frantic call from our cat sitter who said that our keys had been stolen, and that the keys had been in an envelope with our address on it. She had called the police and reported the incident, but there wasn’t much we could do until we got home. While I drove, Carl did a lot of internet research and contacted a locksmith to change our locks first thing the next morning. It was with trepidation that we opened up our apartment, but it seemed to be untouched and Gordon was happy as ever to see us. The next morning, we got a text from the cat sitter that said that she hoped we hadn’t changed the locks yet because the keys had been found at another client’s apartment. That was lucky and saved us a lot of money, but I don’t think we’ll be using that cat sitter again...

Carl and I really enjoyed our brief Easter jaunt into the snowy mountains, but we decided to do things a little differently next year. First of all, we’re going to make sure to go in March instead of April so that we have better chances for good snow. Secondly, we’ve decided that we really prefer solitude to the crowds at Gåsen, so we’re going to make it a point to avoid the weeks around Easter. Thirdly, the long weekend just wasn't long enough to fully get into the rhythm of ski touring, so we're going to make sure to take a whole week off for the trip next year. And thirdly, staying at the cabins is crazy expensive—about $50 per person per night—and again, we really prefer solitude while in the mountains, so next year we very well might take the next step into Adventureland and try out winter camping in the snow!

SUNDAY, APRIL 02, 2017

Living the Life in the Algarve

|

| The house is fairly closed from the driveway side, but it opens up to the ocean. |

|

| Faro's historic monastery and a typical street in the historic district. |

After lunch and a stroll through town, we drove about an hour westward to the rental house, which was absolutely gorgeous. The majority of the holiday houses which have been built along the coast in the last 20 years are gigantic and ostentatious and frankly quite depressing, but this house was tasteful and charming. Stark white with sun-yellow shutters, the house nestles around a patio and pool with beautiful, lush gardens on all sides. Every room looks out over the patio and the gardens to the ocean at the bottom of the long lot. Although the neighboring properties weren’t too far away, we really didn’t notice them because the lush gardens are perfectly designed to block all views and most sounds from intruding in the house’s private paradise.

|

| The view from our bedroom and the view from the living room. |

The house’s lot and all the neighboring lots go almost down to the water’s edge, but not quite all the way to the sea. The water’s edge seems to be public domain, and a rugged walking path follows the cliff’s edge from village to village to village. We didn’t have a chance to follow the path very far, but we did climb up the nearest hill for wide views of the cliffs and sea.

The trip’s timing ended up being a bit unfortunate. While Stockholm was enjoying a record-breaking warm and sunny weekend, southern Portugal ended up being rainy, windy, and unseasonably cold. It wasn’t quite the lounge-in-the-sunny-seaside-garden weekend that we had been envisioning, but we had quite an enjoyable time none-the-less.

|

| Not quite swimming weather. |

One day we drove out to Europe’s southwestern-most point at Sagres. Along the way, we drove through several small towns. It was interesting to see these towns because I had driven precisely the same route 18 years before. At that time, the towns were small fishing villages with just about zero tourism-oriented development. I even pondered buying one beach-side fishing cottage that was on sale for $7000. Today, all remnants of the sleepy fishing villages are gone and the towns are bloated with hotels and condominiums. The towns even have vast suburbs of golf developments with hundreds of pseudo-Mediterranean villas and condos. I was glad to see, though, that the point at Sagres was still lonely and foreboding, especially in the wind-blown rain.

Another day we left the coast and drove up into the Serra de Monchique. More disappointing weather meant that we didn’t get out and explore the mountains as much as we would have liked, but we did spend some time in the sweet Caldas de Monchique which is a small, historic spa village with luxuriant gardens and a tumbling curative stream.

The weather might not have cooperated to our liking, but the Algarve’s seafood just about compensated. Each day we enjoyed a marvelous lunch in a different scenic spot. The ingredients were generally simple, but the preparation was exquisite. In addition, we tried new wines with each meal and were so impressed with the elegant flavors. In the evenings, Carl’s mom prepared wonderful feasts with local mussels, fish, jumbo shrimp, and lamb chops. These meals were also perfectly paired with tasty Portuguese wines. On the whole, I decided that Portugal is bound to be the next hot foodie destination. Italy, France, and Spain are of course already well-known for their food and flavors, but I am convinced that Portugal is next to be discovered.

It was a short but sweet trip. Too short to catch more than a fleeting taste of the area, but it was a very tasty nibble! Thank you to Ylva and Anders for a lovely weekend!

|

| The gardens surrounding the house were full of interesting details and nooks and crannies for sitting and contemplating. |

THURSDAY, MARCH 30, 2017

Off-Piste Skiing in Argentiere

This

year for our French Alps UCPA ski adventure we and several friends went

to Argentiere, which is in the Chamonix Valley. Even though we had

skied the Chamonix Valley together a few years ago, we chose this

destination because the UCPA programs matched our desires

perfectly—advanced off-piste randonnée for Carl and Johan, beginner

off-piste for Jessica, Nora and I. |

| Above the village and in the village of Argentiere |

We really, really lucked out with the snow. In more evidence of global warming’s galloping effect on the European slopes (see my most recent post below, “Skiing Sweden’s ‘Vail’”), Chamonix had next to no snow all winter until the week we arrived, in mid-March. It snowed a couple of meters right before we arrived, and then continued to snow another half meter to meter every day for the first few days of our trip. The first half of our week was definitely not lacking in fluffy powder—powder that ski dreams are made of: light, waist high, untouched. Unfortunately, though, high winds and high avalanche danger meant that all of the Chamonix ski areas were closed one of the days, so we had to travel quite far to Les Houches, a lower and less exposed ski area that is not usually part of the Chamonix ski pass. But UCPA arranged with the ski resort that we would be able to ski Les Houches none-the-less, definitely one of the benefits of skiing with such a large and recognized organization!

|

| Lots of snow and still snowing, from our balcony. |

I also lucked out with my instructor, who was awesome. Sophie was patient, encouraging, and kind; she constantly gave us individualized tips on how to improve our technique; she pushed us but generally not too much; she is uber experienced and impressive on skis but very humble. Slowly but surely, she introduced us to off-piste ski technique, taking us on all kinds of terrain and all kinds of snow and instructing us how to adapt the technique to the varying conditions. Our group was also kind and encouraging and patient which was a huge relief since we were all falling all over the place, and sometimes it takes quite some time to get up, find all your skis and ski poles, and to reattach them to your body, especially when there’s so much powder.

|

| So much snow! |

I took my share of tumbles but they generally didn’t bother me too much since skiing in those conditions was a whole new experience for me. Also, all that powder meant that it didn’t really hurt to fall, even when falling at high speeds. I did have one really bad day, though, but it didn’t have anything to do with a fall. In fact, I don’t think I had fallen at all that morning. But we took the cable car up to Chamonix’s highest point at Grands Montets and then skied quite far away from the piste before really beginning the descent. The slope was steep and exposed, the light was flat, visibility was low, my legs were aching with tiredness, and our instructor warned us to go one-by-one to reduce avalanche risk in a particularly vulnerable spot. I was afraid, and just one too many steps outside my comfort zone. I just lost control and began to have an all-out panic attack—crying, not being able to breath, shaky legs, the whole shebang. It was awful. I’ve never experienced a panic attack before, and it was really, truly awful. But with Sophie’s help from afar, I was able to regain control. It felt like I had been “out” for ages but apparently it was just a couple short minutes. My group was very patient and accommodating and made sure that I always went first, directly behind Sophie, so that I wouldn’t get left behind again. My entire day was shot because I kept having flashbacks to my panic attack, but Sophie managed to talk me calm and to break up the descent into manageable stages. I ended up leaving the group early in order to shake off the negative spiral that my day had fallen into and to rest up for our last day of guided skiing.

|

| We were skiing high, high on this glacier when I panicked. |

And it worked! My last day was brilliant! I still fell, and I still had my tougher moments, but I managed to relax enough to ski comparatively well. I still wasn’t skiing overly gracefully, but I did manage to link up my turns in a relatively even rhythm.

Carl had a good week and enjoyed the powder, the skiing, and the mountains, but he was less impressed with his “lazy” guide. Carl had hoped to walk farther, climb higher, and get more off the beaten track. None-the-less, his group did get some experience with skiing in harnesses, roping up in case someone falls in a crevasse, skinning up mountainsides, and skiing down glaciers.

|

| Carl's group putting skins on to walk up, and his group cruising down again. |

The UCPA center at Argentiere is much more atmospheric than the average center because it is housed in Argentiere’s most historic hotel. While you can’t see the Argentiere Glacier from the hotel any longer, the views are still gorgeous. Carl and I lucked out and even had a room with a balcony! It was of course too chilly to hang out on the balcony, but it was fun to step out and enjoy the view every now and then. The village of Argentiere is quite cute with its historic Alp buildings and very scenic as it is nestled below the craggy peaks.

|

| The UCPA center and our view from our balcony. |

This year, the UCPA program included four intense days of ski instruction and two and a half days of skiing without an instructor. One of the instructorless days found Jessica, Nora and I cruising the slopes at Brévnt-Flégére. The day started out with great views over the valley, but it slowly clouded over and started snowing. The slopes cleared out and we three had the slopes completely to ourselves. Exuberant with the silent slopes and a pure love of skiing, we turned silly and did continuous 360 degree turns down the slope. Then we took the lift back up and did it again, pausing to eat snow flakes on the way.

Toward the end of the week, the skies cleared and the views of the jagged Alps and Mont Blanc’s rounded peak were magnificent. On our last morning of skiing, we took it relatively easy (the slopes were icy and we were all exhausted, anyhow) and enjoyed cappuccinos, hot chocolate, and berry strudel with a vanilla cream sauce in the sun at a very cute, small slope-side restaurant. We couldn’t stop exclaiming over the views.

At the end of our week, all five of us felt pretty finished with the Chamonix Valley (actually, we had felt that way when we were in Chamonix five years ago, too). We were tired of the buses and how you have to sit (or stand, more likely) on busses for large portions of your day to get to the various ski areas. Each ski area is actually relatively small, so you’ve pretty much skiied it all by lunch, but moving on to a different area would require even more bus hassle. We were also depressed by the crowds and for all of the lines. To get on some of the key cable cars, we had to wait in a queue for up to half a day! Chamonix has become too popular for its own good: there are just too many people, too few lifts, and too many people skiing up the off-piste terrain.

Our trip to Argentiere had its ups and its downs, but I am still so glad that we went. The mountains and the scenery were gorgeous, it felt wonderful to spend a week outside on skis, and I am steadily moving closer to my bucket-list goal of skiing hut-to-hut in the backcountry of the Alps. We’re already talking about booking next year’s trip for more off-piste training!

THURSDAY, MARCH 23, 2017

Skiing Sweden's "Vail"

Åre

isn’t Vail, but it is Sweden’s oldest and biggest and most renowned ski

resort, so skiing in Åre has been toward the top of my Sweden-to-do

list since we moved here. This year, we finally made it to Åre for a

four-day long weekend of skiing in mid-February.Although there’s a pretty convenient night train that covers the 615km (almost 400 miles) practically door to door from our apartment, we ended up flying because the train is considerably more expensive than flying, even with the extra hotel night factored in. Silly! We stayed at a very convenient hostel—so convenient that you can literally ski to the hostel’s front door. It’s ski-in walk-out, though, as the lifts are about a 3 minute walk away. In addition to being convenient to the slopes, the hostel is also right in the middle of town, so all the restaurants and cafes and such are within a block or two.

We had a great weekend of skiing despite fairly bad ski conditions. In scary evidence of global warming, the northern mountains of Sweden must be having the least snow coverage on record. Åre’s slopes had about 6 or at most 10 inches of natural snow, and all of the rest was man-made. Considering that this was February and just outside the artic circle, it was pretty shocking that the mountains had so little snow. Temperatures were pretty warm, too, which meant that the slopes were extraordinarily icy. In addition, it was extremely windy (I’m not kidding—nearing hurricane speeds), so what little loose snow there was had long since blown away, and the slopes were left as bare sheets of ice.

The ski conditions were not made better by the weather. Even though temperatures were relatively warm with highs just below freezing and lows around -8 degrees C (17 degrees F), the air was extremely humid, so all of our clothes were constantly damp and we were chilled to the bone. Usually, even in much colder temperatures, I ski in a thin down jacket with a waterproof/windproof shell jacket on top, but in Åre I froze with an artic-puffy down coat on under my shell. Three of our four days were cloudy, so we didn’t have much of a view, and the light was very flat. The crazy wind meant that none of the lifts above tree-line were open, making about a third of Åre’s runs off-limits. I was sad that we never got to see the classic Åre view of the Swedish mountains from the peak of Åreskutan. I guess we’ll just have to try again another year!

|

| Frost from the humid, humid air. |

Despite all the snow trials and weather tribulations, we had a fabulous time swishing down the slopes. I think that’s a testament to how much both Carl and I love skiing! We spent the first day three days exploring the different areas of Åre, repeating some of our favorite runs over and over again. The last day, it finally dawned clear so we decided on a “ski safari” and skied from the middle of the resort to one far end, and then from end to end, and then from the second far end back to our hostel in the middle. It was fun to finally be able to see all the terrain we had been skiing through all weekend, as well as to see the views out over the valley to the mountains beyond.

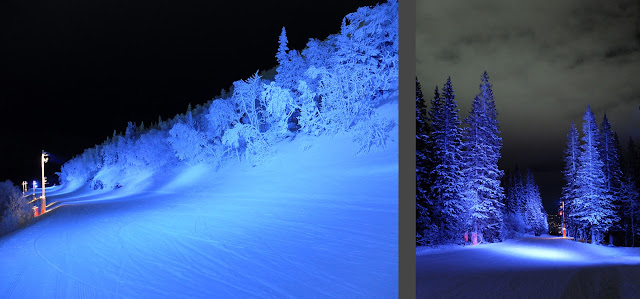

I’ve never been a big fan of night skiing, but I absolutely loved it in Åre. Firstly, the slopes are incredibly well lit—literally better lit at night than during the cloudy days! Secondly, they didn’t just light up the regular runs that go straight down the mountain, but they also lit up a wandering forest run that meanders across the mountain through the snow and frost-covered trees. I thought the blue lighting was a bit cheesy, but still, the experience of skiing through the forest at night was pretty magical and wonderful. Carl and I were freezing, but we repeated the run several times because we just loved it so much.

Ski resorts in Sweden are especially good at being family friendly which is positive even for those of us without kids because it means that the slopes are sprinkled with heated picnic cabins. The cabins are even equipped with microwaves! In addition to the picnic cabins, there are even a number of cute little fire-heated huts throughout the resort. The resort staff keep the fires going so that it’s always warm and cozy to stop in and warm up your hands and feet. Since the conditions were so chilly, we really appreciated all the opportunities to warm up!

TUESDAY, FEBRUARY 28, 2017

Climbing Mayan Pyramids in Guatemala (and Honduras)

As I sit here at my desk and look out at a frosty February Stockholm, our time in Guatemala and Honduras feels like a hazy dream of some imagined past. But Guatemala and Honduras was our reality over Christmas and New Year’s; we spent three days in Honduras and three weeks in Guatemala. In a way, the destination was a bit random—we’ve visited my mom in her Mexican town a few times now, so we planned on meeting up with her in southern Mexico instead. But because there was a lot of unrest in southern Mexico, we decided not to chance buying expensive plane tickets to an unstable area, so we bought plane tickets to the next airport south, which happens to be Guatemala City.

From Stockholm, it was a two hour flight to Frankfurt where we had a five hour layover, then an 11 hour flight to Houston followed by a three hour layover, and finally a three hour flight to Guatemala City where we arrived after midnight on Christmas Day. We were really nervous about arriving in the dicey capitol so late, but the hotel-arranged taxi was waiting for us at the airport and took us straight to the hotel without any murderous detours.

Like many Latin American capitols, Guatemala City is quite dangerous with very high crime rates. Its streets are dirty and its air is polluted and the city is gargantuan in its sprawl of unplanned slums. While there seems to have been a good bit of money and investment in the city in the 20’s and 30’s, today it looks like the money has moved out to the suburbs and that the city has been abandoned to the poor, who make the most out of what little they have. The city is dead after dark with nary a soul to be seen on the sidewalks; even during the day, most streets are deserted and almost apocalyptic feeling. Only the main thoroughfare is lively with a crush of pedestrians—safety in numbers is the rule and no one ventures even a block off this main street.

Guatemala City is home to the national museums, and we were keen on seeing the national archeological museum. This museum is very curated—while it did give a good overview of the objects that have been found in archeological digs from the pre-classic, classic, and post-classic eras of Mayan civilization, the museum is relatively small. There must be thousands upon thousands of objects stored in some secret location. I definitely got the feeling that the museum’s security is not up to the job of protecting the most valuable collections as there were many mentions of jade and other jewelry but not a single specimen on view.

I’m sure there’s more to Guatemala City than meets the eye, but we were much more eager to explore ancient Mayan cities, so we almost immediately hopped on a first class bus to Copan which is just over the border in Honduras. The trip through the little border crossing was quite memorable. Although there’s not much traffic, the border was lazily chaotic with semi-trailers, buses and cars all sitting in the dust waiting for inspection; children wandering around selling citrus fruits, nuts, and candies; mongrel dogs laying in the middle of the dirt road; and black-market money changers accosting new each bus load of travelers—it would have been quite easy to just meander across the border without checking out of Guatemala or into Honduras.

The Guatemalan immigration station was a thatched hut with a porch, and electricity seems to be wasted on nothing but the computers and the very slow satellite internet connection for checking passports. After getting stamped out of Guatemala, we walked across the dirt road to Honduras’s relatively fancy immigration building where they took our picture and our fingerprints in addition to checking our passports. In order to enter Honduras, you have to pay a fee in Honduran currency, but there are no banks or ATMs at the border. Instead, the black-market money changers walk around with huge stacks of cash. We changed just enough money to get into Honduras, but actually, the black-market money changer gave us a far better rate than the bank.

The US Department of State has pretty dire warnings about Honduras:

"Infrastructure is weak, government services are limited, and police or military presence is scarce. . . . rank as . . . the most violent cities in the world. With one of the highest murder rates in the world and criminals operating with a high degree of impunity, U.S. citizens are reminded to remain alert at all times when traveling in Honduras."

Naturally, after reading the State Department’s warning, we were a bit freaked out about going to Honduras, but I am so glad that we decided to take the chance and travel to Copan. Our time in Copan turned out to be a highlight of our trip—the little town was low key and much safer feeling than Guatemala City, even after dark.

|

| Copan Ruinas, Honduras |

|

| Left: Our balcony even had a hammock! Right: the breakfast porch was shaded by these curtains which billowed in the breeze. Gorgeous, and so relaxing. |

the staff was extraordinarily friendly and helpful, and we fell in love with our balcony and our view of rolling ridges of cloud forest jungle.

|

| Morning fog from our balcony. |

|

| Many parts of Copan have been reconstructed, but many other parts are still as found after much of the jungle vegitation was removed. |

We spent almost three days exploring the ancient Mayan city of Copan and several of its outlying areas. Copan is famous for its extremely three-dimensional relief sculpture which has survived far better than its lowland counterparts. While areas like the Yucatan and the Mirador Basin were built with relatively soft limestone, Copan was built with a green volcanic stone that is soft and sculptable when first cut from the earth but which hardens after contact with the air.

The site has 20 or 30 stelae which generally depict a king in full dress regalia on the front and hieroglyphics proclaiming said king’s victories and virtues on the other three sides. Because of their boastful content and their shape with a rounded top, these stelae reminded Carl and me of very large and very complex rune stones. I hadn’t ever realized what a developed written language the Maya had, nor had I realized that linguists have unlocked the code in the last few decades and that we can read Maya stelae. How cool!

Additionally, Copan is famous for its hieroglyphic staircase. Here, an entire staircase up a huge pyramid tells the city’s history. To the untrained eye, this staircase was much less impressive than other sculptures incorporated into the pyramids’ architecture such as squawking macaws, prophetic skulls, grinning old men, a hand holding a bird, and kings running with an “Olympic torch.”

Our guidebooks had prepared us for the wonder of Copan’s sculptures, but it had not prepared us in the least for the sheer massiveness of Copan’s main temple complex.

|

| A model of the massive temple complex. |

|

| Left: View from the ground up to the platform level. Right: View from the platform level back down to the ground. |

|

| Views from on top of the platform up to a pyramid on the left and living quarters on the right. |

Archeologists have dug 18 kilometers of tunnels through the pyramids to access all of the various layers, and tourists have access (for an exorbitant fee) to about 1 or 2 kilometers of tunnel. It was stiflingly hot and humid in the tunnels so we didn’t linger, but it was impressive to see all of those intact layers buried in the pyramids.

|

| In the tunnels. Older pyramid walls are on the left in both photos. In the left-hand photo, the older temple wall is covered in a giant stucco frieze. |

Most tourists probably breeze through Copan in half a day, but having almost three full days gave us plenty of time to sit in the shade, enjoy the view, and contemplate the awesomeness of Copan’s structures. Carl sketched, and I wrote. Mostly we just gazed and admired and enjoyed.

We took the bus back into Guatemala and met up with my mom in the city of Antigua. Antigua was the colony’s first capitol, but after it was nearly leveled in an earthquake in the eighteenth century, Spain ordered the capitol to be moved to a more stable location. Antigua was never completely abandoned, however, and today it is a charming and layered colonial city. The town is exceedingly popular with tourists, and there are hundreds of cafés, hotels, bars, and stores oriented toward gringos. Side-by-side, natives live a more authentic life in the city as evidenced by the crowded, sprawling market.

|

| Faces of the non-touristy side of Antigua |

Antigua is in a bowl of mountains, three of which are volcanoes. One of the volcanoes was even smoking while we were there! I’ve never seen a smoking volcano before, so it was a bit disturbing but very cool. Our hotel was three stories, one story higher than most of Antigua’s structures, so the hotel’s roof terrace had 360 degree views out over the city’s roofs and out to the surrounding volcanoes and mountains.

It also had a beautiful view of Antigua’s beautiful “icing” church. I fell in love with the church’s lemon color and its white icing decorations.

Antigua is famous for its ruins, and we wandered by seven or eight churches, monasteries, and convents which had been destroyed by the earthquake. These ruins provide a charming backdrop to the city’s daily life. Other more recently abandoned buildings are sprinkled about town in a very charming manner and invite one to daydream about restoration projects in lofty colonial courtyard houses. We spent a few days in Antigua and more or less wandered about, stopping at the ruins, the various town squares and parks, and in relaxing courtyard cafes. We did a good job of eating like locals—on New Year’s Eve we sampled street food from carts assembled on the church square, and another evening we ventured into a true hole-in-the-wall restaurant behind the cash register of a mini convenience store where two abuelas (grandmothers) serve tasty down home cooking.

Paying the abuela for our meal turned out to be an interesting experience. Somehow, she has managed to run a successful-enough dining establishment without knowing how to add. When we asked her how much we owed her at the end of our meal, she knew that a meal costs 25 Quetzales. She consulted the convenience store clerk who told her that three meals was 75 Quetzales. But when we reminded her that we needed to pay for our bottle of water, too, she got very flustered. She knew that the bottle of water cost 4 Quetzales, but she couldn’t add 75 and 4 to get a total of 79 Quetzales. We ended up having to help her with the math. Obviously her patrons are an honest bunch; otherwise she would have been out of business long ago.

The abuela who couldn’t add 75 and 4 was actually the second instance during our trip when we noticed an appallingly low level of education among some Guatemalans. The first encounter was at the bus station in Copan, waiting for our bus back to Guatemala. To get through the border, you have to fill out a pretty standard immigration form—name, passport number, origin and destination and such. A middle aged woman in what I would call urban dress—she was certainly no peasant—asked the people sitting next to us to help her fill out her immigration form. At first they thought she needed a pen, so they handed her a pen to borrow. But it turns out that the woman was illiterate and couldn’t read the immigration form or write in her information. She handed her passport to the other passenger and they filled out the form for her.

I’m saddened by these instances of illiteracy, though I’m not too surprised. We saw hordes of children out on the streets begging or playing or helping their parents when they should have been in school. Even the kids in school are most likely not getting the best of educations—I read that a high school diploma qualifies you to teach primary school in Guatemala. Additionally, middle and high school are not free, and the tuition, books, and uniforms are far too expensive for most families to afford.

From Antigua we took a semi-public minibus to Lake Atitlán. From the town of Panajachel, we took a bus-boat to the village of Santa Cruz la Laguna, and from there, it was a 20 minute walk along a rickety boardwalk to our lakeside hotel. Carl was very nice and rolled/carried my mom’s suitcase along the boardwalk. I don’t think he was so amused at the time, but the sight of him rolling a suitcase down the narrow, unstable boardwalk was pretty comical.

Our time on Lake Atitlán was probably the closest to a beach vacation I’m ever going to get. (Carl and I are probably the only “Swedes” ever that fly all the way to Guatemala and don’t even visit the Caribbean or the Pacific beaches!) We had two very calm days at the lake which we mostly spent lounging in the shade, enjoying the view out over the volcano-ringed lake, reading, sketching, writing, and napping. Carl and I did venture out on a walk to the two neighboring villages, but the trails are unsafe past that point so the entire hike only lasted a couple of hours.

|

| Lake Atitlán at sunrise with fisherman and lake at midday. |

Our hotel consisted of a lakeside restaurant verandah and a huge lakeside porch dotted with homemade Adirondack chairs. Small bungalows climb up the steep mountainside along a jungley garden path. Carl and my bungalow was the highest one, and our view out over the lake was just gorgeous. Our room was marginally “inside” but the bathroom was most definitely outside with jungle vines forming a roof and jungle flowers dangling over the toilet. While brushing our teeth and showering, we had a wide open view of the lake, but the bathroom felt totally private.

The hotel restaurant served delicious meals, and we loved sitting on the candlelit verandah with the sound of the water under our feet. I could definitely have stayed in that paradise of calm and beauty for another couple of days, but soon enough it was time for us to make our way back to Guatamala City’s airport for our flight to Flores and our transfer to Tikal.

Visiting Tikal has been on my adventure wish-list for just about forever. Images of the impossibly tall and steep pyramids poking out of the jungle have haunted my daydreams ever since I can remember. I always knew I would visit someday, but I didn’t expect it to be this year—what a great surprise!

Tikal was a giant ancient Mayan city, and today it is the world’s largest archeological site. The archeological park is about 5 km wide and 8 km long, and it is inside of Tikal National Park, which is inside of the tri-national Maya Biosphere Reserve. In other words, Tikal is quite remote and removed from the rest of the world. There are three hotels at the edge of the archeological park, and these hotels have on-site generated electricity from 6 till 8 in the morning and from 6 till 10 in the evening. Crazily, our hotel’s lobby even had functional wireless internet.

|

| Our bungalow at the Tikal Inn |

Unlike Mexico where major archeological sites are swarming with multitudes of vendors desperately trying to sell knickknacks and snacks to tourists, Guatemala’s archeological sites are nearly completely free of commerce and are refreshing oases of calm. The central area of Tikal is about a thirty minute jungle walk from the road, and along the journey, I could feel my tourist tempo slow as the jungle’s rhythm took over.

The heat and thick humidity certainly slowed me, and playing spider monkeys overhead became punctuational pauses in our wanderings as we stopped to find them high up in the trees. The jungle vegetation fascinated us and provided additional reasons to pause and observe. The tempo was occasionally quickened as we hastened to avoid the poop and urine which howler monkeys threw and rained down on us “invaders,” and the excitement of glimpsing Tikal’s pyramids also quickened my pulse.

|

| Spider monkeys!!! |

Tikal is famous for its very tall and steep pyramid (Temple II), which represented a new style for Maya temples. Instead of accentuating the pyramid’s mass, this new style accentuated the pyramid’s height.

|

| Tikal's lofty Temple II |

|

| Tikal's stumpy Temple II |

Tikal’s Temple IV is one of the New World’s tallest pre-Columbian pyramids at 65 meters (212 feet). Because it sits west of the site’s other temples, the sunset view from the temple is just beautiful as the golden glow lights up the pyramids which poke up through the jewel-green jungle canopy. Carl and I spent an hour or two at the end of both days we were in Tikal up on top of Temple IV cooling off in the breeze and enjoying the exotic view. Droves of green parrots flew back and forth in the canopy below us. On our second afternoon, Carl and I bought beers at the unobtrusive water stand at the bottom of the pyramid, climbed up to the top, took our shoes off, and really relaxed up there. Jungle as far as the eye can see, broken only by ancient Mayan pyramids jutting through the canopy.

|

| View from Tikal's Temple IV |

Strangely, Tikal (like many of the lowland Maya cities) was built an a subtle rise in an area with no natural water. No rivers or streams. No cenotes with underground water like on the Yucatan Peninsula. Not even any springs that we know of. Instead, the Maya designed a very complicated system of canals that channeled the rainwater to cisterns and lagoons. This system still functions today and the lagoons are still re-filled during the rainy season and last through much of the dry season. (Where do the crocodiles go when the lagoons dry out?) We later learned at another site the sloping pyramid sides were designed to channel water in a specific way, enhancing its beauty as it jumped from one surface to another.

|

| One of Tikal's still-functional lagoons. |

The large and complex Maya civilization that built up cities like Tikal hung in a precarious balance, and the Maya’s architectural heritage ended up being its undoing. There are only traces left today, but at one time, all of the Maya structures were covered in thick layers of lime stucco. The stucco was sometimes left white, and sometimes it was colored deep red, yellow, green, black, and blue. Large areas of the stucco were made into huge reliefs depicting figures from the religion’s pantheon and mythology. As each new ruler needed to make his mark, new temples and complexes were constantly being built. Not only did this require a tremendous amount of stone and labor, but covering the new structures required a tremendous amount of stucco.

|

| I was fascinated to learn and to see that modern-day Mayans still leave offerings at the ancient Maya sites. |

Creating this lime stucco was no easy task, and it required burning limestone at extremely high temperatures. Studies show that “to cover just one pyramid with stucco, they would have needed to cut down every tree in an area of 6.5 square kilometers.” Although the view from the top of Temple IV is very green today, archeological digs have shown that not a tree would have been in sight at the height of the city’s grandeur. Extreme deforestation in combination with an extended period of drought surely contributed to the nearly simultaneous collapse of all of the region’s Mayan cities around 150 A.D. Excessive consumption led to the civilization’s collapse. We would be wise to remember that history repeats itself.

http://globalheritagefund.org/index.php/news/mighty-maya-cities-succumbed-to-environmental-crisis/

|

| Not everything at Tikal is perfectly reconstructed. |

From Tikal, my mom journeyed back home to Mexico, and Carl and I continued on the adventure portion of our trip which was a six day hike through the jungle to visit several remote archeological sites. We ended up in a group with three other tourists plus a “staff” of three: our guide, our cook, and our muleteer. Carl and I weren’t expecting such a full service trip; instead we were thinking more along the lines of a hike we did in Peru where we hired a guide/muleteer to show us the way and handle the baggage mule. On this trip, it felt really odd to have our meals cooked for us, our dishes washed for us, our tent set up for us, and our bed made up for us. Despite the almost golden-age African safari level of service, the trip was far from comfortable.

It didn’t surprise us, but the jungle was just so uncomfortable and unwelcoming. The heat and humidity were draining, and everything, I mean everything, was practically dripping despite it being the “dry” season. The knee-high mud on some of the trails didn’t make the walking easy, and we constantly zigzagged off the main trail and into the dense jungle in order to avoid the worst of it. (During the rainy season, the mud is chest high and hikers have to pull themselves through mud pits with ropes.)

Weaving through the dense jungle vegetation made for slow going and we were always on high alert for Guatemala’s many poisonous snakes, one of which is the world’s deadliest. I was very thankful that our guide always walked first, and while at the end of the trip he said that he had seen about a dozen, we didn’t see a single poisonous snake the entire six days. I was also extremely grateful for the mules which carried our luggage, food, tents, and water for us—if we had had to carry full backpacks every day, I would have been much more miserable.

Our hike was down in the Mirador Basin which is relatively close to sea level, but the trail undulated up and down, sometimes surprisingly steeply. Distances ranged from 14 kilometers to 36 kilometers per day. 36 kilometers! 22.4 miles! Mosquitoes, ants, ticks, and gnats attacked me constantly, and my abdomen and legs are still covered in red scars.

|

| The hike was uncomfortable, but some of the jungle scenery was fascinating! |

I’ve started with the negative side of the hike, my profound discomfort, but the trek was actually a really memorable and positive experience. Despite being so uncomfortable all the time, I am really glad that we experienced the jungle so viscerally and for an extended period of time. The experience made me even more aware of how comfortable my life is most of the time, and the jungle trek was an experience I will never forget.

|

| Scenes from camp life on our trek. |

On our trek, we visited one major and three junior Mayan cities, but evidence of the Maya civilization was with us nearly constantly. Once we got farther into the jungle, most of our time was spent hiking on ancient Mayan causeways which were built up above the mucky jungle floor. This made for much more expedient hiking, even today when the causeways are covered in jungle vegetation, and the experience of hiking on what is believed to be the world’s first system of “super highways” was literally awe-some. There are 17 known causeways in the region, and they are an average of 40 meters ( 130 feet!!!) wide. The causeways extend for more than 240 kilometers (150 miles) and connect the region’s various cities. We walked about a third of these causeways.

Additionally, small mounds off to the side of the trail were constant signs of Mayan construction. Sadly, most of these ruins have been hacked into by raiders looking for loot to sell on the black market, but our guide told us that the rate of illegal excavations has been abating since tourism started to provide a better living in the region. Round holes in the ground every now and then provided further signs of the Maya. These holes lead through the limestone to larger burrowed caverns where food was stored out of the jungle’s humidity. At one point, we even hiked by an abandoned Maya quarry where limestone blocks were left half-hewn from the bedrock.

|

| Left: Tomb raiders have left their mark on the jungle landscape. Right: an abandoned Maya quarry. |

The more minor sites that we hiked to include El Tintal, Nakbe, and La Florida. These sits are partially excavated and have their own interesting buildings and histories, but I was most intrigued by the sites’ half-excavated pyramids. From the top, you can see out over the jungle canopy to other pyramids poking up out of the jungle. From the first pyramid, we could just barely make out all of the other pyramids we would climb on our journey—the other pyramids seemed to be so, so distant!

Today, undulating ridges of green jungle separate the pyramids and cities, but at the height of Mayan civilization, the jungle would have been non-existent. There wouldn’t have been a tree in sight. What we think of today as “virgin” and “untouched” rain forest and jungle is actually the second or probably the third re-growth after extensive deforestation during the Mayan era. This realization was quite a paradigm shift for me—is there even such a thing as virgin forest, anywhere on the planet?

|

| It's hard to imagine this view without a single tree! |

El Tintal, Nakbe, and La Florida were all subsidiary, secondary cities to El Mirador which was truly gigantic. So gigantic, and so complex, that it has completely shifted the paradigm of Maya studies. Previously, archeologists believed that the height of Mayan civilization was reached during the classic period around 700-800 A.D. But El Mirador is proving that Mayan civilization actually peaked a thousand years before, around 300-200 B.C. The city had 200,000 inhabitants, and close to a million subjects in the network of Mirador Basin cities. El Mirador was probably the largest city in the world at that time.

Not only was El Mirador one of the ancient world’s most populous and powerful cities, but its architectural monuments were unparalleled. Egypt’s pyramids may be taller, but El Mirador’s La Danta pyramid is much more massive, requiring far more building material and construction labor. The entire main plaza at Tikal, pyramids and all, can easily fit inside La Danta’s bulk. La Danta’s lowest platform measures is 3x3 football fields and is 22 meters (72 feet) tall. The pyramid’s peak is 77 meters (250 feet) tall.

|

| The photo on the left is taken from the point of the blue arrow on the right. In other words, the staircase on the left may look gigantic, but it's just the tip of La Danta's iceberg. |

Like Tikal, El Mirador was built in an area of very few natural resources. With no natural water source, all water for drinking, cooking, washing, and irrigation had to be captured from rainfall and stored through the six month dry season. While the jungle may be rich in flora, the jungle’s soil is too nutrient poor to support agriculture. Feeding a million people required extreme ingenuity and the bottom guck of swamps was dug out and piled into highly organized agricultural fields where corn was the most important crop. The resulting holes were plastered in water-impermeable stucco and became important water-storage lagoons.

|

| One of many lagoons that were dug out more than 2000 years ago by the Maya. Today, they look like natural swamps. |

Increasingly complex technology solved El Mirador’s problems of water and nutrient scarcity for more than a thousand years, but eventually, the civilization collapsed because it could no longer feed itself. Signs of turmoil are evidenced in defensive walls, moats, and check points which were built about 100 years before the civilization completely collapsed and the population dispersed at around 150 A.D.

Some 500 years after being abandoned, El Mirador was repopulated and its buildings and monuments were enlarged once again. However, this spurt of activity was short-lived and the site was permanently abandoned by 900 A.D. Due to similar symbolism and nomenclature, archeologists believe that El Mirador’s ruling clan eventually established a new city, Calakmul, which is nearby in Mexico. (It seems that most of the Yucatan’s Maya cities rose to power in the vacuum after cities like Tikal and El Mirador collapsed.)

The city was not rediscovered again until 1926, and it was mapped in 1962. Systematic excavation began in the 70’s and only a small percentage of the site is uncovered today. Excavation is ongoing and every summer 300 archeologists, workers, and support staff dig out a new, small portion of the site. Uncovering a single small pyramid can take 5-10 years; restoration at least another 5-10 years.

We were extremely lucky that we ended up with the guide that we did because he is one of the few guides who takes the summer off from guiding to work on the archeological digs. He has picked up an extraordinary level of knowledge about the ancient Mayan society and about the excavations and was super excited to share his knowledge with us. Luckily, Carl is fluent in Spanish, so he translated our guide’s explanations for the group. Being part of the archeological staff, our guide even had keys to locked tunnels and structures, so we got to go in spaces that most tourists don’t even know exist.

|

| Our guide Enrique on the right. |

Our guide even took us past “Forbidden” signs and barrier fences so that we could get up close to Mirador’s most extraordinary find this far.

|

| Going behind the scenes at El Mirador. |

Because Mirador’s structures were only somewhat uncovered, it was hard to get a full sense of how expansive the city was or of how the individual structures would have actually looked. The city was very formally laid out and while we have an idea about the intentions and the symbolisms and the ceremonies and processions that determined the layout, we obviously don’t understand everything. It’s not strange that the buildings mirror both the hierarchy and the natural phenomenon that were both so vital to the society. The structures were all aligned according to the cardinal directions, and many of them form “skylines” that, when viewed from another platform, mirror celestial bodies at certain times of the year. Many of the structures were also triadic—three tall, steep pyramids were built on top of an already lofty platform.

After our hike, we took a chicken bus (a bus that stops wherever and whenever a passenger wishes, that doesn’t adhere to much of a schedule, that generally services rural areas, and that often transports livestock in addition to human passengers) for many hours from the end of the road back to the nearest airport. I’ve ridden on other chicken buses, even with chickens, but this was my first ride with a chicken on the inside of the bus—in other countries they usually they get tied up on top of the bus’s roof. This Guatemalan chicken seemed perfectly content to sit on his owner’s lap. She just curled up and settled in on her lap, dozing off like a cat.

|

| A typical Guatemalan chicken bus--they are reconditioned and repainted American school buses. |

In addition to chicken sightings, the bus was a good opportunity to observe rural Guatemala. While it isn’t the poorest country I’ve experienced, the majority of the population is quite poor--everyday, grinding poverty that is hard to even imagine. Most people have access to so little money that they have no concept of what it is to have more than a few pennies at any one time. For example, most stores don’t sell bottles of shampoo. Instead, they sell tiny pouches containing one dose of shampoo. Can you imagine a life where buying a bottle of shampoo is out of reach?

|

| Rural Petan, the jungly region of Guatemal. |

Not only are individual Guatemalans quite poor, but most municipalities are penniless—it’s not like they have much of a tax base. One very visible consequence of this is that there doesn’t seem to be any trash collection whatsoever outside of the biggest cities. People just dump their trash down the nearest ravine, onto the street, into the creek, out in the field. At times, rural Guatemala looks like one never-ending trash dump. It certainly puts things into perspective—in the U.S. and in Sweden the conversation is all about how to encourage recycling, while in Guatemala the current challenge is how to collect trash at all.

We had some good meals in Guatemala, but on the whole, I can’t say that Carl and I were overly impressed by Guatemalan food. I was expecting rich, deep flavors similar to southern Mexico, but Guatemalan food seemed pretty bland and not even all that spicy. We were impressed, however, with Guatemalan coffee which is just sublime. We even saw some coffee growing nearby our hotel on Lake Atitlán.

Despite being in Guatemala for three weeks, we certainly didn’t see everything on our list; we didn’t even cover half of our list! I almost always return from a trip longing to return immediately, but this time, I felt like we got a good taste of the country. There’s certainly many more very cool places to experience, but I don’t have the same sense of unfinished business with Guatemala. I wouldn’t say no to returning someday, but as of now, it’s not at the top of my list. That said, I am so, so glad to have experienced parts of the country, especially Tikal and El Mirador, which were extraordinarily special places. It was also cool to experience these places with my mom and with Carl—thank you both for being such wonderful traveling companions!

|

| Guatemalan flag |

WEDNESDAY, OCTOBER 26, 2016

Archi-Dorks in Lyon

A few weekends ago, I travelled to Lyon, France with 14 of my co-workers for a three day binge on architecture. The trip was our more-or-less yearly “study trip,” which is more-or-less financed by the office for the purpose of inspiring employees by seeing new and exciting architecture in person as well as to foster close-knitedness among colleagues. Since we get to choose our destination from a list of about 10 cities every year, I have decided to use the study trips as an opportunity to go cities that I wouldn’t have otherwise visited as a regular tourist. Lyon was definitely one such destination—the city has its charm and some very interesting architecture, but it will never be Paris.

The trip started with a 6:10 a.m. flight, which meant that everyone was exhausted from the get-go. Luckily, the flights and transfers went smoothly and we were soon archi-dorking away in the Calatrava train station (1994) at the airport.

After a late lunch at the city’s food hall (baked mussels drenched in herbs and butter accompanied by a crisp white wine at a food stall’s bar counter, yum!), we spent most of the afternoon and evening wandering around Lyon’s UNESCO World Heritage Old Town called Vieux Lyon. This historic district is apparently one of Europe’s most extensive Renaissance neighborhoods, but while I did note a few late gothic details, I didn’t really see so much that screamed “Renaissance.” I guess that I’ve been spoiled in Verona and in Venice where the Renaissance buildings are much more detailed and much more obviously Renaissance—I’m guessing that those cities were much wealthier and therefore much showier than Lyon.

Vieux Lyon does stand out, however, due to its traboules, or mid-block passages. These passages link up several properties through a series of passages, stairs, ramps, and small courtyards and lead from one street out to the next. Amazingly, several (but not the majority) of these passages are still open to the public, and if you’re in the know, you can push open a seemingly locked door and wander through/under several private buildings. We found about 10 open traboules, and I really enjoyed wandering through them, but I am glad that I was with others because they are dark, narrow, deserted, and potentially very creepy.

|

| A doorway to a traboules, and a typical passageway. |

It was in the traboules that I noticed more Renaissance details—the open-air staircases were especially scenic. Many Stockholmers think that their inner courtyards are small and narrow, but Stockholm’s courtyards are enormous in comparison to Lyon’s New York City light shaft-sized courtyards.

Our dinner reservation was at 9, so we were a very sleepy group that eventually crashed back at the hotel after a very long and full day. The next morning, we were up and out on the town relatively early and visited Lyon’s Roman city ruin which is uphill from Vieux Lyon. The two Roman theaters are impressive, but the museum housing the site’s artifacts is genius (architect Bernard Zehrfuss, opened 1975).

The entrance is at the top of the hill above the theater, and it gradually ramps downward, through the hill, and out to the bottom of the theater. Two concrete and glass portals break through the hillside offering stunning views of the theaters. The French have a long history of beautiful concrete, and this museum was a shining example. Back out at the Roman theater, we were treated to an impromptu concert when a trained opera singer decided to test out the acoustics. After a couple of arias, he started singing happy birthday, in English, to someone in his group, and all the tourists sang along. I’m pretty sure that that girl will never forget her 17th birthday.

After the museum, we broke up into smaller groups depending on which sites we were interested in seeing. It sounds crazy, but the top of my list was an underground parking garage. The garage is a functional parking structure, but it is also an art installation (Targe and Wilmotte were the architects and Buren was the artist, 1994). The garage’s ramp spirals around a circular central core, and large arched openings between the ramp and the core allow views through the core to other levels. At the bottom of the core, the artist installed a rotating parabolic mirror which reflects the powerful space. A periscope in the square above gives a view down to the mirrors. This project was certainly the coolest parking garage I have ever experienced.