TUESDAY, JANUARY 05, 2021

Backpacking Kungsleden's Southernmost Stage from Ammarnäs to Hemavan in the Vindelfjällen MountainsWe

sadly had to cancel our long-awaited Grand Canyon Adventure in October,

a 16-day rafting trip down the Colorado River and the celebration of

our 40th birthdays and 10th wedding anniversary, due to Covid. We had

been saving up vacation days for a long time for this trip, and a week

of those days were about to expire at the end of the year. So we booked

a birth on the overnight train and spent a week backpacking the

southernmost stage of the Kungsleden, or the King’s Trail, which is

Sweden’s version of the Appalachian Trail.

This part of Kungsleden goes through the Vindelfjällen mountains and the Vindelfjällen Nature Reserve. The Vindelfjällen Nature Reserve is Sweden’s largest nature reserve and is nearly three times larger than the behemoth Sarek National Park with its 5,628 square kilometers (2,173 square miles). Vindelfjällen is one of Europe’s largest protected areas, but I couldn’t find information on which areas are bigger.

This part of Kungsleden goes through the Vindelfjällen mountains and the Vindelfjällen Nature Reserve. The Vindelfjällen Nature Reserve is Sweden’s largest nature reserve and is nearly three times larger than the behemoth Sarek National Park with its 5,628 square kilometers (2,173 square miles). Vindelfjällen is one of Europe’s largest protected areas, but I couldn’t find information on which areas are bigger.

We’ve always read that fall is the ideal time for hiking in the Swedish mountains. The colors are beautiful, the crowds non-existent, and the mosquitoes all killed by frost. We did see a few mosquitoes, and there were a number of annoying biting gnats on wind-still evenings, but it was definitely a completely different experience than July when the mosquitoes can be so miserably plentiful that they literally coat your tent trying to get at the warm blood inside. We were surprised by how many people were out hiking in the September cold, and on this less popular stretch of trail, but it was still far fewer than in the height of summer.

The

fall colors were truly amazing. The heath was exploding into red and

the birches were bursting into fiery hues of yellow and orange and red

and the forest groundcover was exploding into color and even the bog

grasses were spikes of gold.

We

hiked during the second week of September, and since the difference in

the amount of color in the forest from the beginning to the end of the

week was marked, I think that next time we have the opportunity for a

fall hike we should try for the third week of September for even more

color and even fewer annoying insects.

Hiking in the fall also had the unexpected benefit of being foraging season! We’ve never done much foraging while hiking, but in the fall, there were too many tasty foraging opportunities to pass up. On several days, we picked a number of strävsop / Boletus and blek taggsvamp / Wood Hedgehog mushrooms and added them to our relatively unexciting dinner menu.

Blueberries

made our morning oatmeal a far more gourmet experience. We picked

fiery birch leaves to make a warming, soothing tea in the evenings.

Our hike began and ended in birch forests, and in between, the trail yo-yoed above and below tree line. I usually far prefer being above tree line, but on this trip, the fall colors (and the mushrooms!) made being in the birch forest just enchanting. Even so, when we did rise above tree line again one day, my heart just sang. Wide open spaces and sweeping 360 degree views is the type of landscape where I am the happiest, something that gets reinforced with just about every mountain trip.

We saw reindeer just about every day. On some occasions, they were in the distance, but on several occasions they foraged fairly close to our tent. What stood out about the reindeer in the Vindelfjäll mountain range was that there were a number of white reindeer. They’re usually shades of brown and grey with some white accents, but I’ve never seen all-white reindeer before.

As I mentioned above, we took the night train from Stockholm up to northern Sweden and got off at the coastal city of Umeå. From there, we had a five hour bus ride straight west to the end of the road at Ammarnäs. As usual, I was so impressed by how convenient and how far out in the middle of nowhere you can get on Swedish public transportation. It poured the entire bus ride and continued to rain for the rest of the day. It wasn’t the clear, sunny day we had dreamed of, but the views into the misty valley had their own atmospheric appeal. The hike started in the small village of Ammarnäs, rose up through the forest, crossed a raging river in a ravine (yay for bridges!), and quickly ascended to tree line with views out over the valley. Once above tree line, significant stretches were through a bog—again, thank goodness for all of the excellent bog bridging!

We

set up our tent a few kilometers above the first mountain cabin and

Carl surprised me with a half bottle of wedding anniversary champagne! I

still can’t believe he hiked the champagne all the way up the

mountainside!

The next day also dawned wet, but again, we enjoyed the misty views. The trail continued climbing until we reached a high, windswept plateau and then undulated up and down the plateau’s bumps past several alpine lakes. Even though the low clouds covered much of the surrounding mountain scenery, the plateau felt alpine and isolated and wild. The heath was glowing with autumn red and was just breathtaking. The plateau reminded me of the hike we did a few years back on Isle of Skye along the Trotternish Ridge (see “Summer Vacation 2018 Part II: Isle of Skye”)

Toward the end of the relatively long day, the trail descended back into the birches, crossing another wild stream. The bridge (thank goodness there was a bridge!) was perched just above a huge waterfall.

Again,

we passed the mountain cabin and set up our tent a bit farther along

the trail alongside a slowly meandering creek. By that evening, the

rain had dried up and we were able to sit out by the creek and enjoy the

scenery while journaling, reading, harmonica playing, and drinking

birch tea.

Our third morning was sunny and we enjoyed a relaxed breakfast in the sun. As we started walking, though, a few isolated clouds started to roll through, and by lunch a bank of clouds had entirely blocked the sun. There was no rain, however, until the evening.

Once again, the trail rose up onto an alpine plateau. But this time, we had views of some of the surrounding peaks and to the snow-spotted mountains in the distance. We’d be walking through those snowy peaks the next day.

Again, the trail eventually descended to a forested valley, but instead of a raging river, this valley was filled with a long lake, Tärnasjön. We stopped at the next hut at the lake’s edge to replenish our food supplies, then continued hiking along the lake. We bushwhacked from the trail back to the lake’s edge to try to find a waterside camping spot. The shore turned out to be mostly covered in uneven, jagged slabs of rock that made it impossible to set up a tent. We spent quite a while continuing to skirt the shore until we found a spot that was just barely campable. It was quite sloped, but we did have a water view! We had purposely chosen to camp in the lee of a peninsula because the wind along the lake was bracing to say the least, but it turned out that our camp was so wind still that the biting gnats were out in droves. We sat outside for a while but eventually retreated into the safety of our mesh tent.

The next morning, we did have some sunshine as we continued to walk along the lake’s edge, but by lunch we were eating in the cold, drenching rain. The base of the lake drains through a series of islands before narrowing into a river, and the Kungsleden trail uses these islands to hop across the lake. A series of seven highly engineered bridges meant to withstand the force of huge icebergs hurled at the structure by the force of a violent spring thaw kept our feet dry while crossing the lake.

On the other side of the lake, the trail again rose above treeline. It was here that my heart began to sing joyfully at the wide open landscape and views.

We

still had a lot of energy when we reached the next mountain cabin, so

we asked for tips about where to camp. The hut warden told us that the

next pass was likely to be very windy that night, but we might have luck

with finding some wind shade up at the edge of the eastern glacier

below the Syttertoppen peak. We started up the mountainside with a

spring in our step, but the hike soon began to feel endless. The higher

we rose, the farther the glacier seemed and the stronger the wind

became. It started to sleet, and the wind became so strong that gusts

forced us to stop hiking and concentrate on staying upright. But we

kept hiking up and up and up despite the wind and the sleet and the ache

in our calf muscles, and eventually we reached the glacier. It was

pretty anticlimactic, however, because the low clouds blocked all but

the lowest edge of the glacier and we couldn’t see the peak.

After searching a bit, we found what we believed to be wind shade. We set up our tent and climbed in to change out of our soaking wet clothes. But shortly after we climbed into the relative warmth of the tent, the wind surged and the gust collapsed our tent. We were able to get it upright again, but another gust collapsed the tent poles again. And again. And again. We quickly realized that camping up at the glacier in our somewhat flimsy summer tent was not going to work so we took the tent down and starting hiking. Instead of walking all the way down to the cabin to pick up the trail, we shortcut across the mountain’s shoulder and joined the trail at the pass.

By this time, it was dark, we were still being slashed by sleet, we were soaking wet and freezing cold, and the wind was still gusting enough to knock us over. There was nothing to do but to continue down from the pass, stop for a quick snack, and then continue hiking on toward the emergency wind shelter that was halfway to the next mountain cabin. When we made it down to the next valley, we were devastated to see that the river’s bridge had been destroyed and that construction on the next bridge hadn’t gotten farther than a pile of lumber. Luckily, the river was just about rock-hopable, and our boots were soaked anyway, so we just slogged through.

After fording the river, the trail rose up toward the next alpine pass and the emergency wind shelter. Along the way up to the pass, I was chanting “please be empty, please be empty” but when we got there, there was already another couple taking shelter. Luckily, the emergency shelter had two berths that were wide enough to sleep two people head-to-foot. After hanging up our sopping clothing on lines crisscrossing the shelter, we cooked dinner in the shelter’s vestibule and went to bed. It was hard to sleep with wind gusts so strong that they were shaking the entire structure. Considering that the shelter’s roof was anchored to the ground with steel lines, it seemed likely that the building would survive another storm, but you never know. No building lasts forever.

The next morning, the wind was still fierce but it had died down to the point that the building wasn’t shaking with each gust. Our clothes hadn’t dried one bit, so we put our wet clothes back on and stuffed the rest of our sopping gear back into our bags. Considering the sodden state of our gear, we decided to spend the next night at Viterskalsstugan, a mountain cabin just a half day’s hike away.

The hike to the cabin was through a deep, glacier-carved U-valley. The clouds were low and covering the peaks towering above us, but through the mist, we could still sense the alpine drama of the landscape around us.

It

was a quick hike to the cabin and in no time we were checking in and

had most of a day spent drying out our clothes in the wood-fired drying

room, taking showers with wood-stove warmed water, sitting by the cozily

crackling wood stove, drinking tea, and gazing at the horizontal rain

outside the windows. It was such a luxurious day!

That evening, the clouds cleared out enough that we could see the rocky mountaintops around us. We hiked about a kilometer back into the valley to see the full dramatic view complete with sunset colors.

It’s good that we took advantage of the clearer weather the evening before, because Day 6 dawned rainy and cloudy, and the peaks were once again hidden from view. Despite the dreary weather, we left the cabin and set up our tent about a kilometer away and then went on a day hike up a side valley. Our original destination was a lake that the cabin host had recommended, but we didn’t feel like crossing a raging river to get there so we continued up the valley instead. As we rose in elevation, the rain changed from drizzle to solid rain to snow. So much for our dry clothes, it didn’t take long for my clothes to become rather wet again despite my rain gear.

Where the grass and heath gave way to rocks, we huddled in the lee of a giant boulder inside our wind sack and ate a frigid lunch. Once we were moving again, rock hopping up the valley, it took a very long time for us to warm up again. The snow and wind continued to rage around us as we climbed up the last steep wall of rocks to get to the base of the western glacier below Syttertoppen peak. Once again, we could only see the bottom part of the glacier because most of it was hidden behind clouds. The wind sweeping off the glacier was freezing so we had a very short fika break sipping tea and coffee from our thermoses before beginning the long hike back down the valley to our tent.

We were really hoping for a clear day the next day so that we could climb up to the top of Syttertoppen peak. But sadly, the day dawned once again rainy and cloudy, so we decided to have a snoozy rest day of reading in our tent. A bit after lunch, however, the weather cleared a bit and we decided to make an attempt at the peak. The trail climbs quite steeply and we gained altitude and a bird’s-eye view over the valley in no time.

After

about 20 minutes of climbing, the grass gave way to rocks, and after a

total of about 45 minutes of climbing, we hit the snow line, and the

hiking became slow and slippery. After just a short time in the snow,

we decided that the risk of slipping in the snow and falling off the

side of the mountain was all too likely, so we turned back. We had made

it approximately half way up to the peak.

On the way back down to camp, the clouds moved in and it started raining again. More wet clothes!

Day 8 was also rainy and wet. It was our last hiking day and we had an uneventful but wet hike as we walked out of the valley and down to the small town of Hemavan. The last few kilometers were across Hemavan’s ski hill. It’s not a particularly big ski resort, but it still took us a good hour to cross it. When we’re swooshing on downhill skis, we don’t really notice just how much ground we’re covering, but the speed and ease of skis hides the fact that we are actually crossing a great deal of distance.

All of the other start/end points of the various Kungsleden stages have cozy mountain stations with gourmet, locally sourced food. Hemavan was a big disappointment in that there was no mountain station, and because of Corona and a shortage of tourists, none of the town’s better restaurants were open. We had an entire afternoon to kill before our bus back to the train was due to leave, and it was heavily raining and quite cold outside, so we went into the one open restaurant in town and staked a claim in one of the diner’s booths. We changed out of our soggy hiking clothes and hung our sopping rain jackets, socks, and clothes all around the booth and on the adjacent radiator. I’m sure the locals have seen it before, but it was still quite the scene with all of our clothes strewn about. Luckily, the restaurant was hopping and it took forever to get our giant burgers and baskets of fries. We ate veerryy slowly, then sat and lounged a bit. When it felt like we couldn’t just sit there any longer, we ordered desert and ate that vererryy slowly.

Eventually, it was time for our four hour bus ride back to Umeå and the night train to Stockholm. We showered on the train (the showers are always fantastically clean and the train even provides towels and soap and shampoo!) and then went into work the next morning. At work, I changed into the work clothes I had stashed there, then went about my working day.

Including our side hikes, we hiked about 105 km or about 65 miles from Ammarnäs to Hemavan. It’s really not a huge distance over eight days, and little of the hiking was particularly challenging or strenuous. We had chosen this hike in part because the scenery promised to be gorgeous and in part because we were feeling a bit exhausted after all our/my trips to Mexico and the US to help my mom out over the last year. Also, we weren’t crazy about the idea of fording deep rivers in the chill of autumn, and the civilized and developed nature of the Kungsleden meant that almost any unhopable stream would be bridged; most of the wet, boggy areas were sure to be bridged, too. We luxuriated in the leisurely pace of the hike—taking as long breaks as the weather allowed, spending the long afternoons and evenings reading, picking mushrooms and berries, enjoying the fall colors and the mountain scenery. Adventurous hikes at high altitudes or without trails are certainly exciting, but leisurely, “civilized” hikes certainly have their place, too.

SATURDAY, DECEMBER 19, 2020

Fall Weekend on SvartlögaCarl’s

aunt invited us out to her cabin on the archipelago island of Svartlöga

in September. Being relatively late in the season, there was no Friday

evening boat so we took the ferry out on Saturday morning and then home

again on Sunday evening. It was a short weekend, but very relaxing and

quite lovely.

The spring and summer had been relatively dry, but there was some rain in the early fall so we were hoping to find mushrooms in our secret spot. However, a hurricane-strength windstorm had blown through since the last time we had been on the island, and parts of the forest were a totally unrecognizable chaos of downed trees. We never did re-find our secret spot (we should have recorded GPS coordinates!) but we did find a good number of mushrooms, mostly autumn chanterelles, anyway.

Which was a good thing, since our planned dinner was mushroom pizza baked in the cabin’s wood stove! The pizza was exuberantly delicious and we had such a lovely candlelit evening enjoying food, wine, and good company.

Fall was underway the island with cooler temperatures and yellowed leaves and golden reeds at the water’s edge.

The spring and summer had been relatively dry, but there was some rain in the early fall so we were hoping to find mushrooms in our secret spot. However, a hurricane-strength windstorm had blown through since the last time we had been on the island, and parts of the forest were a totally unrecognizable chaos of downed trees. We never did re-find our secret spot (we should have recorded GPS coordinates!) but we did find a good number of mushrooms, mostly autumn chanterelles, anyway.

Which was a good thing, since our planned dinner was mushroom pizza baked in the cabin’s wood stove! The pizza was exuberantly delicious and we had such a lovely candlelit evening enjoying food, wine, and good company.

Fall was underway the island with cooler temperatures and yellowed leaves and golden reeds at the water’s edge.

Both

days we went on short exploration hikes and even stopped at some our

favorite spots on the charming island. What a lovely weekend, thank you

Eva!

FRIDAY, DECEMBER 18, 2020

Short Gotland WeekendA

couple weeks after our summer vacation ended, Carl and I took the ferry

to Gotland to visit his parents. They had been “hiding” from Corona on

the island since the spring and were of course still wary in August.

Instead of hugging when they picked us up from the ferry terminal, we

waved to each other.

We had a beautiful evening on the ferry on the way out to Gotland, and we spent the first half of the journey out on the deck drinking bubbly. When the bubbly was finished and we were starting to get chilly, we retired to our chairs and had a relaxing evening of reading. The last time we had been on the Gotland ferry it was with my wonderful friend Melinda, and I thought of her a lot during the trip.

We had a beautiful evening on the ferry on the way out to Gotland, and we spent the first half of the journey out on the deck drinking bubbly. When the bubbly was finished and we were starting to get chilly, we retired to our chairs and had a relaxing evening of reading. The last time we had been on the Gotland ferry it was with my wonderful friend Melinda, and I thought of her a lot during the trip.

Saturday dawned less beautiful, but we did manage to beat the rain and go for a walk with Carl’s mom at Sigsarvestrand, a waterside nature reserve a bit north of their house. We had a lovely walk but had to turn back a bit prematurely due to the rain; we made to the car just as it started to pour down fat drops.

We

spent the rest of the day relaxing in front of the fire and reading.

In the evening, we enjoyed an incredible crawfish feast!

The weather was a bit better on Sunday—not much sunshine but at least not a lot of rain, either. Carl’s parents are working on visiting every nature reserve on Gotland (there’s 141 of them, so it’s not a small feat), and we tried to go on a hike at one of their new favorites. But with all the recent rain, the usually dry stream beds were raging so we cut the hike very short and enjoyed a picnic instead. During the picnic, we were intensely watched by a sea eagle who circled around to and from its perch in the pines overhead several times.

Carl’s parents are also working on visiting all of Gotland’s 92 medieval churches, so we “helped” them visit three. We were excited to see Tingstäde Church which had been on our list not least of which due to its medieval farm gate.

While

we were in the area, we also drove by another medieval farm gate at

Riddare. I love that not just so many buildings, but so many other

parts of the medieval cultural landscape survive on Gotland.

It’s hard not to find interesting prehistoric sites while wandering around Gotland, and this trip was no exception. We stopped at Rings i Hejnum to see ruins of farmhouses from about 200-300 A.D. Like many iron age houses in Scandinavia, the main house was huge—40+ meters or 130+ ft long! The modern day farmhouses are just 100 yards away—the continuity of the farming landscape on Gotland is just incredible!

Before heading to the ferry, we walked a bit in another nature reserve, this time Södra Hällarna. This nature reserve hugs the west coast and one could walk along the coast for several days before exhausting the strung-together nature reserves—definitely worth another visit and a longer hike!

All too soon our time on Gotland came to an end and we had to head with the ferry back to Stockholm. But we’ll be back! Thank you Ylva and Anders for another lovely Gotland weekend!

Many

hilly areas of Sweden, from north to south, are rich in iron, and iron

has long been one of Sweden’s most important industries. Sweden’s Iron

Age began around 500 B.C. when locals began to process ore gathered from

bogs. This was a very local phenomenon—the process was so inefficient

and produced such small quantities of iron that farms produced iron only

for their own needs. Somewhere around 500 A.D. (probably earlier), a

more efficient blast furnace enabled people to produce iron that was

much stronger and more workable. The real breakthrough for Sweden,

however, was the early Middle Ages (around 1100 A.D.) when iron began to

be mined from the earth. Suddenly, quantities exceeded local needs and

Sweden’s iron began to be exported throughout Europe. Local techniques

were still quite antiquated and inefficient, however, so Sweden

imported experts in the latest technologies from the Wallonia region of

Belgium. By the 1600’s, the combination of extensive mining of iron ore

and the advanced Walloon techniques meant that more than 40% of

Europe’s iron was exported from Sweden, and Swedish iron was regarded as

the world’s highest quality product.

While the production of iron from bog ore began as a very localized phenomenon, larger mining operations required a complex organizational hierarchy. It didn’t take long for the crown to claim ownership of all ore under the earth’s surface, and mining the ore required special permission from the crown. In the beginning, these privileges were given to groups of locals to cooperatively mine their local ore. These groups were called “bergslag” or “mining teams.” But as the business grew more and more profitable, shares of the cooperatives were bought up by businessmen or doled out as favors to those loyal to the King. The cooperatives quickly became corporations owned and run by a wealthy elite, and Bergslagen came to denote the mining region of middle Sweden more than the cooperative teams. In some cases these wealthy elites happened to also be nobles, but most nobles weren’t interested in dirtying their hands with the business of mining (they probably didn’t have the cash, either) and most often these Bergsmän or “Mining Men” were commoners. Ownership of mines and ironworks was one of the very few ways for the non-aristocracy to gain wealth and status in Sweden.

While the focus of Bergslagen was the mining and refining of iron ore, there were a number of necessities that supported iron production. Without waterpower to power the hammers as well as navigable waterways to transport the iron, charcoal to heat the blast furnaces, and grain to feed the workers and their families, there could have been no iron production. Waterpower and navigable waterways required the construction of lake systems and canals as well as advanced mechanical waterwheel and lock systems; charcoal required forests, lumberjacks to fell the wood, and charcoalers to produce the charcoal; and grain of course required farmers with enough of a surplus to sell to the ironworks communities. The iron industry called for the symbiosis of extended communities and extensive natural resources. A single large ironworks with a couple hundred workers was supported by a larger community of thousands of people as well as hundreds of miles of forest.

I don’t know the exact number, but I would guess that during Sweden’s golden age of iron production in the 1600’s and 1700’s, there were about 100 large ironworks in middle Sweden (concentrated in the regions north and west of Stockholm). These ironworks were located at the junctions of important natural resources—near the mines, on navigable waterways, and in the middle of vast forests. For these reasons, the ironworks were located nowhere near the cities, and their locations were seen as being in the middle of nowhere, far away from “civilization.” Before the establishment of the ironworks, these areas were extremely scarcely populated, meaning that the ironworks communities were built from scratch.

Many of these new ironworks communities were planned and built by the owner patrons. Much in the spirit of some of the 18th century industrial reformers in England, Sweden’s ironworks were built as model communities where the workers were given decent housing, the children were educated, the elderly were cared for in “retirement homes”, medical services were provided, goods were purchased in the company store, and everyone was expected to attend services in the village church. I think that while the working conditions were fairly brutal with long hours and backbreaking work, the living conditions at these ironworks were actually better than for the average working-class Swede.

Being a product of the Enlightenment, these ironworks communities were designed in a logical and orderly if not entirely symmetrical manner. The patron’s grand mansion and surrounding gardens were often the focus in the middle of the complex. The mansion and grounds were often design by star architects from the Swedish cannon. The overseer’s house bridged between the patron’s mansion and the workers’ housing in both location and size. Workers’ housing consisted of identical buildings marching at a steady rhythm down a street, and behind the dwellings were barns and storage sheds for the workers’ livestock and equipment. To the one side of the complex was an axially placed church. To the other side of the complex were the industrial buildings.

I was struck by how close the owner’s mansion and gardens were to the industrial buildings. These would have been noisy, dirty areas producing massive amounts of air and water pollution. Today, desirable residences are always well separated from noise, dirt, and pollution-producing activities. But at the dawn of the industrial revolution in the 1600 and 1700’s, the noise, dirt, and pollution were signs of wealth and success.

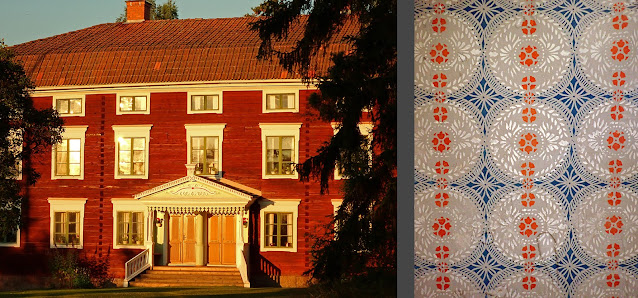

The mansions of the four ironworks that we visited were all renovated or built in the mid-1700’s. I was struck by how conservative these buildings were in design. While the palaces of the royalty and the aristocracy were moving toward extremely sedate, classical facades and low, invisible roofs at the time, the industrialists’ mansions were renovated/built in the Baroque style that had been popular 50 years before—detailed facades with round windows as well as extremely high roofs in the style of French chateaux. With their mansions, one understands that while the industrialists may have been technologically advanced, they were followers when it came to social and aesthetic norms. They wished to join the ranks of the established aristocracy, not to create a new social elite.

The first ironworks of our trip (and also where we spent the first night) was Österbybruk in Uppland just north of Stockholm. Österby was Sweden’s second-largest ironworks and just about everything from the mansion to the gardens, from the industrial buildings to the workers’ housing, and from the lake and canal system to the storage sheds remain.

The

interior of the mansion is not in excellent, original shape and the

gardens are just a bare outline of their former glory, but I was pretty

astounded to see just how intact the entire ironworks district still

is. And while the historic district is no longer used for mining and

iron production, the village is still an active mining and iron

community with a large mine and several different modern iron production

facilities. Österbybruk is fairly unique in that its industrial

complex is not only intact, but is still in working order.

The mansion complex consists of three buildings: a main residence with protracted wings to both sides, an older kitchen building, and a chapel. The oldest building is from the at least the 1600’s (probably earlier) and many additions were made over the generations but the current Baroque facades were designed by Erik Palmstedt in the 1730’s (I’m not sure about the date, it could be 1760’s).

|

| Österbybruk's mansion's kitchen wing, front facade, and interior. |

The industrial buildings are from the 1600’s and were renovated in the 1700’s. The workers’ housing also dates to the 1600’s.

I’m

not sure when the wagon “carport,” horse barn, or orangeri were built

but together they create quite the charming atmosphere.

There

was also quite the amazing entry portal into the area consisting of two

rounded buildings at the end of an axial row of storage sheds. These

rounded buildings recall the corps de logi, the quarters for the palace

guards, at Stockholm’s Royal Palace.

Today,

the mansion house is used for offices and a museum, one of the wings is

a B&B and gourmet restaurant, the workers’ housing is rental

apartments, the orangeri is the boutique for a beautiful, extensive

commercial garden, and many of the various barns and storage sheds are

cafés and boutiques for local handcrafts.

|

| Storage sheds at Österbybruk |

Next, we visited Lövstabruk which is only a few miles from Österby. Lövsta’s grounds and the interiors of Lövsta’s mansion are still in perfect condition, but the industrial buildings were torn down when the ironworks shut down in the 1920’s. Lövstabruk was Sweden’s largest ironworks and its prominent status is well visible in the magnificent mansion complex with its incredible gardens and scenic canal. The original village including the mansion were burned down by the Russians in 1719, but the patron rebuilt according to the original village plan and even in the same Baroque style. While the original mansion and wings were constructed of wood, the new mansion was built of slightly more fireproof brick.

Österby’s mansion sits scenically beside its lake and canal system, but Lövsta’s grounds are integrated with the waterways. The canal flows directly in front of the mansion, and two small pavilions flank the mansion and line the water. One of the pavilions was the library—what a beautiful setting for reading, writing, and contemplating!

Lövstabruk also has a rounded “corps de logi” where the servants had their quarters.

|

| The back side of Lövstabruk's mansion and its "corps de logi" |

The

“industrial” side of the estate was on the other side of the beautiful

gardens. Closest to the patron’s mansion were the ironworks office, the

church,

|

| Lövstabruk's church |

Slagsten,

or slag stone, is a byproduct of melting ore to extract the iron—the

remaining slush was poured into forms and hardened into building blocks

which are nearly black with iridescent green and blue nuances. Slag

stone can be found throughout the estate in building foundations, in

fence posts, etc.

Not

only are the byproducts to be found throughout the estate, but the iron

itself is prominent in fence railings, gates, flower urns, etc.

|

| Lövsta's iron products proudly on display |

Today, Lövsta’s mansion is a museum, the various barns and storage sheds are rented out as boutiques and small businesses and ateliers, and the workers’ housing is rented out as private apartments. Sadly, the mansion’s interior was closed due to Corona so we’ll have to go back another time.

Our third bruk or “works” of the trip was Söderfors bruk.

While

the ironworks is older, the entire estate complex was redesigned in the

mid-1700’s by star architect Carl Hårleman. He even gave the patron’s

house a face lift.

The church, finished in 1792, was designed by another star architect Erik Palmstedt.

At Österbybruk, the workers’ housing marches to the side of the patron’s mansion, while at Lövsta, the workers’ houses march parallel to and in front of the patron’s mansion. At Söderförs, the worker’s housing creates an axial “allée” marching to the patron’s mansion.

Behind the workers’ houses are more barns and storage sheds made of slag stone.

Söderfors is most well known for its English garden. Unfortunately, the garden is now split in two by the main road and fast-moving traffic, but you can still get a feel for the tranquil, riverside retreat. A wooden copy (in smaller scale?) of the Theseum in Athens is in the middle of the park (built 1797). Of course, the base of the temple is slag stone.

|

| Söderfors bruk's English garden folly |

Today, the Söderfors mansion is a hotel badly in need of a paint job, on the exterior at least.

|

| The backside of Söderfors bruk's mansion faces the water |

We then journeyed a good distance west to the region of Västmanland to visit the UNESCO World Heritage ironworks at Engelsbergs bruk. Like all the ironworks we saw, what you see today is only the most recent incarnation of a 700+ year long history. The patron’s mansion was rebuilt in 1746 after the older house burned down, and the industrial buildings were renovated to accommodate the latest technology in the 1870’s. Like Österbybruk, Engelsbergs bruk is still in working order.

|

| Engelsbergs bruk's industrial coplex from the 1800's |

While there are some buildings left, it seems that most of the workers’ housing and many of the storage sheds and barns have been demolished. Today, it’s hard to get a sense for if Engelsberg was built according to a structured plan like Österby, Lövsta, and Söderfors or if it grew up more organically. The buildings that do remain, however, are slightly less refined than the other ironworks we visited. They are still beautiful, but the exposed log-cabin timbering was a less exclusive finish than the stucco of Österby and Lövsta or even of the wooden paneling of Söderfors.

|

| The overseer's house at Engelsbergs bruk |

But what was really impressive in my eyes were the mansion compound’s

two

round pavilions built of glimmering blue-green slag stone. One of the

pavilions was the outhouse, and the other was a pleasure pavilion for

small dinner parties and the like. Here, the slag stones are made to

look more rectangular with the subtle beige paint filling out the parts

of the expected regular form. Bright white-painted “joints” between the

stones reinforce the illusion of uniformity.

|

| Engelsbergs bruk's round slag stone pavilious |

One thing that struck my is how idyllic these ironworks districts are today. By design they are off the beaten path and far from cities. They are quiet and charming; it’s like time has stopped in these communities. The ironworks are all integrated with scenic waterways. I wonder how much of this sense of a country idyll was present in the 17th and 18th centuries. Or was the water and air too polluted to be enjoyed?

|

| The lake at Engelsbergs bruk |

It hadn’t been on our original to-see list, but while at Engelsbergs bruk, we read about a nearby archeological site where Iron Age blast furnaces from about 385 A.D. reinforce that iron has been produced in the area for millennia. To my eyes, the artifacts aren’t super impressive, but I am impressed by how ancient these smelting furnaces are, and that they have survived though the centuries, and by how the archeologists could even know what they were looking at.

Visiting a few of the ironworks in Uppland and Västmanland was our last mini-adventure of summer vacation. In between our overnight adventures, we also explored a few other sites on day trips from Stockholm including a really cool hilltop fortress, Broborg Fornborg outside of Knivsta;

Linne’s Hammarby outside of Uppsala,

kayaking to the canal and “hidden” lake at Ulvsunda Slott,

visiting a prehistoric ridgetop "fenceline" of standing stones,

and foraging stone berries on the island of Adelsö; and foraging cherries, red and black currants, and gooseberries in the forest.

and foraging stone berries on the island of Adelsö; and foraging cherries, red and black currants, and gooseberries in the forest.

We

did have some relaxing moments this summer—snoozing in our hammock in

the midst of a blueberry forest, picnicking atop a prehistoric hilltop

fortress, lazing amidst the cows in a sunny shieling, reading and

looking out at the water in Sankta Anna Archipelago—but we did do quite a

lot of touristing, too. I loved getting to see more of the cultural

historical sites closer to home, but I did miss going on a big hiking

trip, completely disconnecting from life, and the being amidst

incredible mountain scenery. I think the lesson here is that we just

need more vacation in order to do both!

All of the photos are my own except for the Engelberg mansion photo (the building was under scaffolding when we where there) which came from Wikepidia and the Linne's Hammarby interior photo (no photography allowed inside) which came from:

http://www.alaintruong.com/archives/2016/01/13/33208863.html

All of the photos are my own except for the Engelberg mansion photo (the building was under scaffolding when we where there) which came from Wikepidia and the Linne's Hammarby interior photo (no photography allowed inside) which came from:

http://www.alaintruong.com/archives/2016/01/13/33208863.html

WEDNESDAY, DECEMBER 02, 2020

Kayaking the Sankta Anna Archipelago: Summer Vacation 2020 Part IVWe

enjoyed our little trip to Falun but we were also getting a bit tired

of touristing. So for our next last-minute local-ish adventure, we

decided to focus on nature instead of culture. The Sankta Anna

Archipelago has been on our kayaking to-do list for a while now—there’s

an article about kayaking there just about every year in Sweden’s

version of Outside Magazine and the area seems to be a bit of a mecca

for kayaking. It’s a bit far for a weekend trip and getting there

requires a car, so our summer staycation with rental car convertible

seemed to be the perfect opportunity to finally check out Sankta Anna.

Like the Stockholm Archipelago, Sankta Anna is a cluster of islands where Sweden’s mainland dissolves into the Baltic Sea. The water around Sankta Anna is much shallower, however, so the area is not great for large motor boats or sailboats. Kayaks, however, are the perfect form of transportation!

The Sankta Anna archipelago is also different than the Stockholm Archipelago in that it is much more compact. Unless you’re an expert and can cover a lot of distance in a day, paddling from the mainland to the outer islands of Stockholm is a several day journey. But in Sankta Anna, even an average paddler can paddle from the inner to the outer islands in a day. This meant that in our four days of paddling, we could really cover a huge portion of the archipelago without really paddling much at all. We only paddled 2-4 hours per day and spent the rest of the time reading and relaxing.

We spent the first two days paddling toward the outer edge of the archipelago, meandering through the islands and exploring quite a lot of territory. We definitely did not paddle in a straight line from kayak rental to outer islands! We then spent most of a day paddling out at the archipelago edge before turning back in and heading more-or-less toward the mainland. On the way back, we did quite a lot more meandering, exploring lots of new-to-us canals and islands. One goal was to repeat as little territory as possible.

While I think my favorite paddling is though small, winding canals between islands, I always love paddling out past the last islands to see the water meet the horizon. Before paddling out of the protected water behind the islands, the water was a bit choppy but didn’t feel dangerous at all. But as soon as we got out from behind the islands, half meter waves pounded our boat. I don’t think we were in any actual danger of flipping over, but I was very, very nervous anyway. We circled some rocks quite a ways outside of the islands and then paddled back into the relative calm behind the islands.

|

| This photo was actually taken on a much calmer day than the day we ventured out past the last protective islands. |

One literal and figurative high point was kayaking to and climbing up Missjö Kupa, the archipelago’s highest point. Looking down on all the small islands dotting the sea all the way to the horizon from this peak was almost like getting a bird’s eye view. (Wonder if one day people will say “drone view” instead?)

|

| View from Missjö Kupa |

Despite being a paddling mecca and despite the kayak rental outfitters being fully booked, we only saw a few other kayakers over our five day trip. There were some motor and sailboats in the area, but not many at all. This was a very stark contrast to the Stockholm Archipelago which would have been absolutely crawling with visitors at the height of the summer. We definitely enjoyed the luxury of our mid-summer solitude!

Having just about every island in the archipelago to ourselves, we could be choosy when picking our campsites. Of course we only picked tent sites that were worthy of making an outdoor magazine cover! We have a tendency of taking the tent spots with the best view, even if they’re not super level. We figure that we get to sleep in a level, comfy bed just about every night of the year, so when we’re out paddling, we want to see and hear the water as much as possible. Our bed at home does not exactly have a water view or wave soundtrack.

| |

| Camp day 3 |

|

| Camp day 4 |

We had quite varied weather over the trip: Blazing sun and not even a breeze with glassy water. Blasting wind and driving rain with half meter waves. Overcast skies and choppy seas. Sun so scalding that we wore long sleeve shirts and sun hats to keep from burning. Wind so chilly that we wore our puffiest down coats at camp. A little bit of everything.

We swam from camp a couple of times. The water was refreshing to say the least but it felt so good to soap off the sweat and grime of paddling and camping, and then to sit in the baking sun to dry off and warm up.

By this time toward the end of summer, sunset wasn’t toooo ridiculously late. We stayed up and watched the magnificent sunsets every evening. Thank goodness for our puffy down jackets, our wonderfully comfy camp chairs, and box wines! It might just be the most relaxing moment ever, so sit in a camp chair, alternately gazing out over the water and chatting and then reading, sipping on wine, nibbling on chocolate, waiting for the pinks and oranges to develop in the sky.

Between the sunset lounging, the dearth of other paddlers or boaters out

and about, the short paddling distances, and the mostly good weather,

this may have been one of the most relaxing paddling trips ever. We

usually paddle over a weekend or long weekend, but on this 5 day trip we

were able to fully ease into the tranquil rhythm of Sankta Anna’s

archipelago.

Continuing

on a UNESCO World Heritage site theme, our next little summer trip was

an overnight to the town of Falun in the region of Dalarna, a couple

hours north of Stockholm. Falun is the site of Falu Gruva, a copper

mine that was actively mined since at least the 700’s, probably even

earlier, all the way until the last round of dynamite was exploded in

1992.

While I’m not generally particularly interested in mines, Falu Mine was exceptionally important in Sweden’s history. While the mine’s history goes back to Viking times and probably even earlier, its golden age was in the 1600 and 1700’s when Falu Gruva was the source of two-thirds of the world’s entire copper production. Falu Gruva, together with Sweden’s extensive iron exports, was almost single-handedly responsible for Sweden’s wealth at this time and made it possible for Sweden to become the empire-building power that it was in the 1600’s—at that time, Sweden stretched from Norway into Russia, from the Artic Circle down into Poland. The mine was the largest workplace in Europe with its 1300 workers. Because of the mine’s long, uninterrupted history and because of its importance to both Sweden’s and to Europe’s economy, Falu Mine is now a World Heritage site.

The mine didn’t originally have a big open pit. Instead, it was a labyrinth of hundreds of kilometers of tunnels leading hundreds of meters underground. But on Midsummer Day in 1687, the mine collapsed, creating the huge cavity that is about 400m in diameter and 100m deep. Because it was Midsummer and a holiday, no one was in or around the mine and miraculously, no one was killed.

The mine is open for guided tours, and while we walked only a tiny fraction of the mine’s tunnels, it was pretty fascinating to experience just how extensive the mine is as well as how large some of the rooms are. That was a lot of pick pick picking through history until dynamite was invented in the 1800s!

Above ground, a good bit of the mining landscape still remains. Heaps of discarded copper colored ore.

Buildings made of slagsten,

or slag stone, a byproduct of melting ore to extract the valuable

metals—the remaining slush was poured into forms and hardened into

building blocks which are nearly black with iridescent green and blue

nuances.

An impressive headquarters with chapel from the 1700’s.

Given

that the mine was so important to Sweden’s economy, it’s not surprising

that the town around it grew into Sweden’s second largest city in the

1600’s. When the town was finally granted an official city charter, the

older medieval town was rebuilt into a more modern city with straight

streets and regular blocks. This city from the 1600’s is still visible

today, and the area closest to the mine which housed mine workers is now

a part of the UNESCO site.

Falun’s profusion of smelters refining the ore into copper produced a black smog that notoriously hung over the city. It may have been economically important and Sweden’s second largest city, but Falun wasn’t a desirable place to live. Instead, those with the means, including of course the mine’s investors, lived on estates outside of the city. A bit downstream from the city, Gamla Staberg is a typical one of these estates and is therefore also part of the Falu Mine UNESCO World Heritage site.

In addition to its other superlatives, Falu Mine is also the world’s oldest stock-owned company, dating back to at least 1288. I’m not exactly sure of the details, but it seems that the mine was owned by investors, each of whom had a right to dig in the mine. It seems that before more modern times, there wasn’t really one central mining company directing operations; instead it was more-or-less every investor for himself. An investor hired workers to work his share of the mine, and the ore dug up by his own workers belonged to the investor himself. In some cases, the investors had smelting operations right in Falun. But in other cases, the investor’s private smelting operation was located on the investor’s estate, where the owner could more easily keep an eye on things. This was the case at Gamla Staberg, which is both a grandiose estate and an industrial site. Ore was easily transported over the lake from the mine to the estate, smelted into copper, and then transported down the river to markets in Stockholm and beyond.

To our eyes, Gamla Staberg doesn’t look very grandiose. The house and its wings are only one story, and they’re wooden buildings instead of stone. But when they were built at the end of the 1600’s, they would have been very impressive to the average person in Dalarna where the climate was cold and the small farms not terribly profitable. The house was built around the year 1700. In Stockholm, fashion was turning away from the heavy Baroque style toward lighter Classical forms. But in the “wilds” of Dalarna, fashions were a bit behind the times and the Gamla Staberg estate house was built with twisted Baroque columns and a Baroque garden on axis with the house.

We had a wander around the garden and the estate, but we spent most of our time at Gamla Staberg up on the hillside picking blueberries and lazing about in our hammock under the pines. By this point in our summer vacation we had already done a good deal of touristing, and we were feeling a bit worn out. It was a lovely break to linger in the forest reading, snoozing, and berry picking.

On a bit of a side note, there’s yet another aspect to Falu Mine’s importance. Sweden’s landscape is literally dotted in red cottages and red barns, and this iconic red color is called Faluröd, or Falu Red. The paint pigment is a byproduct of the Falu mine, and the metals in the paint help to preserve wood. Before Falu Red paint began to be produced in the mid 1700’s, the vast majority of Sweden’s buildings were unpainted and the exposed wood became grey after a few years in the elements. Historically, Sweden’s built landscape was a very grey one. But starting in the mid 18th century, Sweden’s built landscape became very red. While the paint cost money, it was more cost-effective to buy the paint than to replace the wood more often.

Of course, others soon learned the secret recipe to make the miraculous Falu Red paint, but the color is still colloquially known as Faluröd and the official name is still legally restricted to paint produced by the Falu Mine (while the mine isn’t in use any longer, the company still makes the paint).

SATURDAY, NOVEMBER 14, 2020

Painted Farmhouses of Hälsingland: Summer Vacation 2020 Part IIWhile the Oak Landscapes of Östergötland south of Stockholm (see below) are a byproduct of the landed gentry in the area, Hälsingland’s Painted Houses are a byproduct of the lack of landed gentry north of Stockholm. There’s a Swedish saying that the oak and the noble aren’t to be found north of the Dalälven river, which is just a bit north of the capitol city, and it’s true. For most of Sweden’s history, the climate north of this river boundary was too cold and the land was too unproductive to be attractive to the aristocracy. No nobles were given or assembled large estates up there, the result being that farms were owned by locals and no rents had to be paid to estate owners. Whatever wealth was in the land was able to stay with the locals.

And the local wealth was invested in architecture. Specifically, in farm houses. It’s not all that different that the aristocracy, really, who hired star architects and tried to outdo each other with their luxurious country residences. But of course the scale was different for these painted farmhouses, as were the materials and methods. While the nobles’ houses were palaces created by name-brand architects and styled according to the latest international vogue, the painted farmhouses were created by uneducated artists and craftsmen in a vernacular interpretation of long-stale fashion.

|

| Built by two brothers with two separate residences under one roof, Jon-Lars is the largest of Hälsingland's farmhouses |

I don’t write the above to diminish Hälsingland’s painted farmhouses. In fact, the level of artistry, skill, and beauty that is achieved is all the more impressive given the relatively humble circumstances surrounding their creation.

|

| Pallars and Ol-Anders farms |

Being able to hold on to its own wealth was one major factor for Hälsingland’s relative prosperity. Another two important factors were flax and forestry. Flax has been cultivated in the region since at least 200 A.D., but it was time-consuming and required a great deal of brute force to refine the flax into raw materials for linen. It was simply too complicated to make a profit off of. But a couple of inventions in the 1600’s and 1700’s meant that water could provide the power instead of men and beasts, and suddenly flax became a profitable crop. All of Sweden clamored for Hälsingland’s linen—no one needed fewer clothes, after all. The farmers of Hälsingland made large profits off flax from about 1700 to about 1850 when imported and inexpensive cotton began to enter the market.

|

| Erik-Anders |

Forestry was another major source of wealth and coincided with the waning of flax’s golden age. Since ancient times, the forest was never owned by a person; it was collectively used by the community, but there was never any need to define ownership over the forest’s vast land or resources. Individuals cut the wood that they needed for their own buildings and hearths, and no more. In this way, the forest regenerated itself in a sustainable manner—there really weren’t all that many people, hearths, or buildings in the region so the demand for the forest’s natural resources wasn’t all that high.

|

| Gästgivars |

Even though cities such as Stockholm had had wood shortages for centuries, there hadn’t been an effective way to transport timber from Sweden’s northern regions to the cities. That changed with the advent of the train and the steamboat, and suddenly Hälsingland’s timber could be easily transported to Stockholm and the forest-poor regions of southern Sweden. Suddenly, the question of forest ownership became important. The state divided up the forests among the surrounding farms, and each farm received enormous areas of forest, for free. The farmers then contracted out their forests to sawmills which gave the farmers a good deal of money for “nothing”—the farmers hadn’t had to do even a day’s work to receive these large sums. Eventually, much of the forest was bought up by forestry concerns, giving the farmers another big injection of cash.

|

| Kristoffers and Ol-Nils farms |

Between flax and forest, Hälsingland’s farmers accumulated large profits from about 1650 to about 1900. As I wrote above, these profits were generally invested in farmhouses—banking didn’t really even exist in the region at the time, and hiding money under the mattress was certainly no safe alternative. Better to paint your house and outdo your neighbor! While farmhouses did generally get bigger and fancier over the period, there were two main concentrations of ostentation: the front stoop, and the party salon.

Pimping the front stoop was a very local phenomenon. While the various villages of the region all had their own local style of front stoop,

|

| These similar wooden stoops are from the 1600's on the left (Karlsgården) and from the 1700's on the right (Delsbo forngård) |

|

| Jon-Lars |

|

| Pallars |

The party salon was an almost universal fixture in Hälsingland’s painted farm houses. First, it has to be said that the tradition of a rarely used “Fine Room” was common in Sweden. All but the poorest of tenant farmers traditionally had two-room farmhouses where one of the rooms was the kitchen/dining/living/bedroom and the other room was a seldom used parlor for special occasions like weddings and baptism celebrations. But Hälsingland’s farmers took this “Fine Room” concept to a whole new level and often built entire buildings dedicated to nothing but occasional celebrations. In some cases, the party building was only ever used once to celebrate a single wedding!

These party salons and sometimes even the entire interior of a whole party building were painted by travelling artisans. Depending on the village, the wall paintings might be murals depicting exotic scenes, murals depicting Biblical stories, stenciled geometric patterns, or stenciled floral patterns. The range of the paintings is enormous, but all are incredibly well executed and most are very colorful. Sleek Scandinavian design in shades of grey is a decidedly modern phenomenon. These interior paintings were a cheaper imitation of the extremely expensive silk and paper wallpapers that were used in the aristocrats’ palaces from the 1600’s onward.

The Painted Farmhouses of Hälsingland are a UNESCO World Heritage site in part because there are over 1000 of them still remaining. Another contributing factor is that so much of the historical cultural landscape is still intact

—the villages, the barns and outbuildings, the farms and fields, the streamside flax threshing sheds, etc.

|

| Västeräng |

Even

much of the original furniture, kitchen equipment, and farming

equipment remain in place. Also important was the fact that so many of

the farms have been in the same family for at least 14 generations and

probably more—written records only go about 14 generations back. Even

so, only seven of the farmhouses made the cut to be included in the

actual World Heritage listing. During our four days in the region, we

managed to visit about 16 farms (three only on the outside because they

were closed due to Corona) including six of the official World Heritage

farms.

|

| Left: Bed/Clock/Desk at Gästgivars. Right: a small sample of all the original items at Pallars |

While the farms themselves have for the most part not changed boundaries since the Iron Age, the oldest farmhouses we visited were from the end of the 1600’s. The exterior of these buildings have a distinctively medieval character despite being well past the Renaissance and show just how slowly things changed in the relative isolation of Hälsingland’s interior. These buildings are generally unpainted on the exterior, only one story, and are much more modest than the later and more famous “Wooden Palaces” from the mid-1800’s. The paintings from the end of the 1600’s were decidedly baroque in style and less flamboyant in coloring than their later counterparts.

|

| A farmhouse from the 1600's and its interior painting, Delsbo |

By the mid-1700’s, the houses started to grow and the paintings began to get a little more colorful,

|

| The building on the right is from the 1700's. Its party salon. |

|

| Fictionalized

scenes from the cities of Västerås and Gävle as well as Sami Lappland

at Pallars. It's probable that neither the artist nor the patron had

ever been to those places |

|

| Jon-Lars |

On the slightly simpler side there was a good bit of marbling, such as at Pallars and at Erik-Anders,

But what I really fell for where the repeating geometric and floral motifs. My absolute favorites were these very famous patterns at Gästgivars and Kristofers which have been filched and made into wallpaper patterns.

I was also struck by these slightly more complex patterns at Gästgivars.

And this classic, foreshadowing contemporary Sweden’s love of muted, grey, wintery tones.

The fanciest paintings were painted onto a canvas of sackcloth which was stretched over the walls, but more cost-saving paintings were applied directly to the wall’s wooden boards such as these at Ol-Anders and at Delsbo.

As if the wall paintings weren’t colorful enough, a common theme was that there was a border at the ceiling with a completely different pattern and color palate. In my modern eyes, these borders just clash and detract, but an 19th century eye thought that more is always better.

On

an additional colorful note, the region is also known for the “wainscot

paneling” which aligns with the window sills. Here, the “paneling” is a

very provincial interpretation of the paneling which can be found in

palaces throughout Europe. In Hälsingland, the boards are impressively

wide but don’t have any three dimensional effect like in the palaces.

Instead, they’re painted, sometimes in a solid, bright color and

sometimes they’re painted to look like expensive wood such as walnut or

mahogany. I really loved the paneling in Hälsingland—it helps to

emphasize the low height of the window sills as well as the tall

proportions of the windows, and creates a dado around the room. And I

found the mismatched sizes of the panels to be really heartwarming—while

these party buildings were built to impress the neighbors, the farmers

still made do with the materials on hand and saw no need to waste wood

in order to make perfectly consistent paneling boards.

|

| Gästgivars and Bommas |

The farmhouses of Hälsingland are known for their painted interiors and front stoops, but the buildings are just bursting with interesting details. Everything from locks and door handles to door panels and hinges were painstakingly crafted, and every detail emanates the craftsmens’ care and pride in creating these objects.

|

| Details from Ystergårn |

In every farmhouse, I noticed the incredibly wide floor boards. It was easy to see that these buildings were built before the forest began to be cut down in an industrialized manner.

|

| Kristoffers |

While all of the farmhouses were built with advanced log cabin techniques, the exteriors of these large 19th century farmhouses are not completely uniform. Some leave the logs exposed, some are paneled, some are painted in Sweden’s traditional red oxide paint which preserves the wood, and the most modern facades are painted in new-fangled light tones which were only became available toward the end of the 1800’s.

|

| Log cabin details from the 1600's (Karlsgården) and from the 1800's (Jon-Lars) |

Some of the farm houses have more modern terracotta tile roofs, but a number of the farmhouses still have more traditional wooden roofs. At Karlsgården, the roof is still long planks of wood over a waterproof layer of birch bark. The planks cross at the roof ridge. At Ystegårn, the barn is still covered in wooden shakes.

Even in the 1880’s, there were still some building traditions dating back to the middle ages. While windows in Stockholm had long been built of wood, windows in Hälsingland were still fashioned with lead mullions, even after the panes of glass had become larger.

|

| Ol-Anders and Kristoffers |

Traditionally, Hälsningland’s farmhouses, party buildings, and barns formed a completely enclosed rectangle around a central courtyard. During the 1800’s, however, the rectangle was commonly opened up on one side.

One

enclosing barn was removed, opening up the courtyard and the farmhouse

to the landscape and creating more of a manor-like atmosphere as Swedish

manor houses were nearly always built as a “U” with two flanking

wings.

Very

few completely enclosed Hälsinge farms remain, but Gästgivars still has

one of its double enclosures, and both Karlsgården and Ystegårn are

still enclosed on four sides.

Nearly all of the sixteen farms we visited are still inhabited by families. People live their everyday lives in these farmhouses, and they still use the party halls for baptism and Christmas celebrations. The farms are still productive, working farms and many of the barns are still in use to store equipment and to shelter livestock. The residents are clearly attached to their farms and their farmhouses—the farms have been passed down in the same family for generation upon generation and the farmhouses are in many cases little changed except for a few rooms which have been modernized with plumbing and electricity. Often, our tour guides were a member of the owning family, or a neighbor. One of the most memorable moments of the trip was having fika, coffee and cake, by a blooming rose bush out in the courtyard with the owner of Bommars. It was such a lovely and personal way to learn about the history of his family’s farm.

We planned this trip only two or three days beforehand so disappointingly we didn’t get a room in one of the Hälsinge farms that rents out rooms (some rooms even with original paintings!). But we did stay in a bed and breakfast in Långhed within walking distance of two of the UNESCO farms. It ended up being a great choice because the B&B owner knows the owners of those farms and was able to give us a private tour of the farmhouses despite them being officially closed due to Corona. The last night, we stayed at a beautiful hostel outside of Ljusdal. Because of our lack of planning, we ended up driving back and forth between the same points a few times, so it wasn’t the most efficient trip ever. But we did get to know those stretches of Hälsingland pretty darn well!

While we did concentrate on the region’s famous farmhouses, we did see a couple of other sites (all in wood!) that illustrated a few more aspects of traditional country life in Hälsingland. First was a collection of 33 small, individual horse stalls at the edge of the region’s main river. Here, farmers left their horses and took the ferry across the river to church.

I also really loved this church bell tower in Delsbo.

We

also visited a shieling up in the forested hills above the fertile

farmland down in the river valleys. In the summer, livestock were

moved uphill from the farm to summer pastures. Several farms

collectively shared the summer pastures and built a little summer

village of tiny cottages and barns for the livestock and their keepers.

This tradition died out by the 1960’s but a few of Sweden’s fäbodar or shielings still serve their original purpose.

I totally and completely fell in love with both Hälsingland and its farmhouses. Perhaps its my quilting background, but the stenciled patterns are works of art that just pierce my being with loveliness. And the landscape with its long cultural history is both beautiful and fascinating. I am so glad that this region has received a level of protection, and I hope that the region continues to be valued for its incredible vernacular architecture.

WEDNESDAY, NOVEMBER 04, 2020

Oak Landscapes of Östergötland: Summer Vacation 2020 Part IEven

before Corona, Carl and I were planning and hoping for a summer

staycation. First of all, we’re just exhausted after all that life has

thrown at us the past couple of years and the thought of planning and

going on a big adventure was a little daunting. Secondly, we didn’t

have anyone to stay with or take our cat. And thirdly, so many of the

local sites are best in the summer, or only open in the summer—since

we’re always gone for Stockholm’s one month of summer, we have never

managed to experience many of the sites close to Stockholm.

Once Covid became a thing, it became even more apparent that we really didn’t need to fly to the US for vacation, so our desire to stay in Stockholm this year turned out to be in keeping with the times. However, many of the sites in a ring around the capitol city were closed due to the virus, but most sites just a little further out were open, so we had to twist our original plan a bit. Instead of lots of day trips, we ranged a bit farther a field.

Once Covid became a thing, it became even more apparent that we really didn’t need to fly to the US for vacation, so our desire to stay in Stockholm this year turned out to be in keeping with the times. However, many of the sites in a ring around the capitol city were closed due to the virus, but most sites just a little further out were open, so we had to twist our original plan a bit. Instead of lots of day trips, we ranged a bit farther a field.

Covid threw us a much-appreciated curve ball: because just about everyone was staying in the Stockholm environs this year, and few people have cars in the city, the rental car agencies were completely out of cars. We had booked our economy car well in advance at a very cheap price, but when we got to the rental car counter, there were no economy cars left. Instead, we got a convertible! I’ve never given much thought to convertibles but it was SO MUCH FUN! I feel so middle aged. We managed to have the top down for at least a part of every day.

Our first excursion of summer vacation was to the Oak Landscapes of Östergötland, a few hours south of Stockholm. Once we were far enough south, we exited onto the small, winding back roads, many of them one lane and gravel, and pretty much didn’t drive on a numbered road for the rest of our journey.

This region of the country is known for its Oak Landscapes. Oaks aren’t really a natural phenomenon in Sweden’s climate, but with a bit of coaxing, they grow to magnificent size and age in the southern third of the country. Oaks have been an important part of the cultural landscape for millennia; their timber was always valued for construction, their acorns have always been a valuable part of the diet of swine, and their majestic appearance has almost certainly always been a delight to the human eye.

Today’s oak landscapes are an interesting byproduct of history. Dating back to the middle ages, both oaks and beeches were protected trees in the local law traditions. Private citizens were not allowed to cut down oaks or beeches even on their own private property: instead, these trees were so valuable that they were only allowed to be used for the common good. In the 1500’s, King Gustav Vasa formalized these local traditions into a countrywide law where oaks, even on private property, were the property of the Crown to be used only for shipbuilding. The one exception was the landed gentry, who were allowed to use their own oaks. The result was that most farmers didn’t bother to cultivate the finicky and time-consuming oaks. What was the point of spending all that time and energy to grow trees for the Crown’s sole use? But because the landed gentry were allowed to use the oaks they cultivated, they purposely planted and maintained oak groves. These rules were in place until 1938!!

This resulted in a lopsided landscape where oaks were concentrated onto estates. And because relatively few of the estates in Östergötland have been developed in modern times, much of the oak landscape remains.

Over the course of two days, we explored four different estates/nature reserves. Most of the estates seem to still be privately owned and used by private families, but the oak landscapes have been turned into nature reserves open to the public.

The most impressive estate was Sturefors, built at a small fall where a river falls into a lake, which was on my to-see list for its architecture as well as for its oaks. The original house which dated back to at least the 1300’s is long gone, but the current house was designed in 1699 by star-architect Nicodemus Tessin the Younger.

Tessin

also designed the formal French gardens, but the picturesque English

garden with its folly was designed in the 1770’s. Carl and I enjoyed a

lazy picnic, a nap, and then a lazy fika in the sunny gardens.

Not only are the architecture and the landscape architecture striking, but Sturefors’s oak/farm landscape is just stunning. With white puffy clouds overhead and sprawling green oaks on the ground, the landscape was a quintessential picturesque rural landscape.

Another interesting estate was Brokind, also built at a small fall between two lakes. There was originally a medieval castle here, but it burned in the mid-1700’s and a new, “modern” house was built.

|

| The Brokind estate, main house and mill house on the falls |

While we were in the area, we also stopped by Ekenäs Castle. Ekenäs means “Oak Ridge” which is quite appropriate for the area! The defensive position of this steep hill beside a lake (now unfortunately drained) was used for millennia—Ekenäs was built in the late 1500’s displacing a medieval village, which had in turn been built on the site of a prehistoric hilltop fortress.

Ekenäs

castle is no where near as big as Sweden’s other surviving Renaissance

castles, but those were built by kings while this castle was built by a

mere nobleman. The landscape was once dotted with numerous private

castles from the Middle Ages and from the Renaissance period, but very

few of them remain, making Ekenäs quite unique.

|

| Hard to imagine what the fire insurance costs! |

This trip we stayed in a hostel in another estate house but on a much more modest scale than Sturefors, Brokind, or Ekenäs. After enjoying a bottle of wine on the balcony overlooking the lake, we learned that the property was officially alcohol-free. Good thing there were no other guests to offend—the hostel was crazy quiet.

While we did get a good taste of Östergötland’s Oak Landscapes, there are many more oak-filled nature reserves in the area to explore! And many more country roads to zip along! Maybe next time we’ll have to book a convertible on purpose...

TUESDAY, NOVEMBER 03, 2020

Vadstena Renaissance Castle + 3 Medieval Cloisters, 2 Nature Reserves, 2 Standing Stones, 6

Runestones, Bronze Age Petroglyphs, 11 Medieval Churches, an Iron Age

Stone Circle, and a Really Cute Medieval Town

We

had a 4 ½ day weekend in the middle of May for Ascension Day so we

rented a car and drove about three hours south of Stockholm to the

medieval town of Vadstena to check out its picturesque castle and the

surrounding countryside. As usual, we managed to pack quite a lot of

history and culture into the trip, but we also spent two days hiking in

the area’s nature reserves.

Vadstena was already an established town when Sweden’s most famous saint, Birgitta, established a new order and convent in the 1300’s. The King and Queen donated their royal palace on the edge of town so that Birgitta could establish her convent there. In return for the donation, the royals were to be buried in the church and forever after receive masses on the anniversary of their deaths. The town expanded as the convent became a pilgrimage destination for pilgrims across Europe. The “perpetuity” of death masses only lasted about 200 years because after the Reformation, the convent was closed and the church used for Protestant services.

|

| Birgitta's Church and part of the medieval cloister |

It was at about this time that Vadstena Castle was built in 1545. Sweden’s other impressive Renaissance castles were already existing defensive structures which were renovated and modernized to meet the day’s military needs, but Vadstena was built new during this unstable period when Sweden was wrestling itself as a sovereign nation from the Danish. Its location not too far north of the Danish border and protecting the very important shipping route of Vättern Lake was quite strategic, but it was never actually used for defense or battle.

|

| Vadstena Castle's exterior |

The

castle was originally a wall to the lake with a couple of small

buildings incorporated into the wall, but its defensive structures were

quickly expanded and in 1550 the buildings were connected and built up

into a Renaissance palace forming the impressive structure that remains

today. The various phases of construction are still visible in the

façade.

|

| Inside the castle walls |