MONDAY, APRIL 09, 2018

Ski Touring in Jämtland

Ski Touring in Jämtland

This

year, my dear friends Chad and Tom were supposed to join us for a week

of hut-to-hut ski touring in the nearly arctic mountains of Jämtland,

Sweden. But when Tom’s mom suddenly fell ill, they were forced to

cancel their trip. Carl and I were really, really bummed that they

weren’t able to join us, but we did manage to have a wonderful week

despite their absence.

After

our third ski touring adventure, Carl and I feel like we’re starting to

get the hang of it. Bad weather (up to a certain point) doesn’t feel

as threatening, distances don’t feel quite as far, we don’t fall as

often, downhills don’t feel as frightening, we are better able to

control our skis, and the entire concept of skiing through the arctic

mountains doesn’t feel quite as foreign and exotic as it did just a

couple of years ago.

Granted, we are still skiing on marked paths and between warm huts. We didn’t run into any truly horrendous or scary weather on this trip. We had access to plentiful food and even hot showers at many of the huts.

Although we are getting more into the swing of ski touring, this trip still had its challenging moments. Our most challenging day was 24 kilometers long (we find 20 km to be quite enough), the wind was strong, the visibility was poor, and the snow was deep and un-compacted for 11 kilometers. Instead of being able to glide along, we sank one to three feet through the snow with each plodding step. Each step required us to lift our heavy ski up and over the snow, and each time the snow didn’t bear our weight our energy levels and spirits sank a little bit lower.

|

| Limited visibility between Vålåstugorna and Helags fjällstation |

When we finally did get back onto compacted snow and were able to glide forward as one expects to be able to do on skis, we were jubilant and filled with energy and skied quickly for about 2 kilometers. But when we had about 3 uphill kilometers left until the hut at Helags, ie 21 kilometers in to an utterly exhausting day, we slowed down considerably and Carl turned to me and said that he had “lost his exuberance.” I felt the same way. The promise of a gourmet dinner awaiting us at Helags spurred us forward, if slowly. But by the time we got to Helags Mountain Station, it was too late to sign up for dinner. I nearly burst into tears from exhaustion and disappointment.

|

| The cabins at Helags Mountain Station |

Another challenge was blisters. As usual, our rental boots tore up our feet and my heels were painfully blistered. My right heel had two quarter-sized blisters, and my left heel had five dime-sized blisters that over the course of the trip melded into one giant, oozing sore. Disgusting and painful, but luckily none of the blisters got infected.

The weather at the beginning of the trip was fairly mild with a highs of -8 degrees C (about 17 degrees F), but by the end of the trip daytime temperatures had dipped to about -20 degrees C (-4 degrees F) in the valleys and were even colder up on the passes. Only at one point did the cold feel very threatening. That day the sun was shining but the wind was fierce. Luckily the wind was at our backs so we didn’t have to fight it with every step, but it did make even a short stop dangerous. We had climbed up to a high plateau and then coasted for quite a distance slightly downhill. Coasting downhill was simply not enough work to keep me warm, and my fingers and feet began to throb with cold. We were tired and hungry and thirsty, but stopping was just not an option.

|

| View back to Sylarna mastiff on the way toward Blåhammaren |

Luckily, most trail segments between huts have an emergency wind shelter for just such conditions—they allow you to get out of the wind, rest, and replenish your energy stores with food and water before moving back out into the harsh wind. The wind shelter was full of people when we got there, but they scooted in and made a bit of room for us. The shelter wasn’t warm so my toes continued to be worryingly cold, and we ate a very quick lunch and then skied on our way again. The trail continued downhill to my cold dismay for a little while, but it did eventually go uphill again. It only took a few minutes of uphill before my toes began to tingle with feeling and I was warm enough to start shedding layers.

|

| Standard model of emergency wind shelter |

When we were about halfway up that hill, the wind, which had been severe all day, suddenly disappeared. The air was completely still and without the wind, the sun was warm and inviting. Even though we had had recently stopped for lunch, we stopped and sat on our packs, enjoyed the view out over the mountains, sipped coffee and tea from our thermoses, and nibbled a bit of chocolate. It felt like the eye of the storm, and it must have been some weather phenomenon like that, for the breeze picked up again while we were sitting, and once we were back on the trail, the breeze transitioned into a full wind again. By the time we reached Blåhammaren Mountain Station, the wind was practically at gale force again and it took both of us to open the hut’s door against the wind.

For each challenge, we were also granted a joyfully lovely day. Our second day out began with a gorgeous sunrise and views under the clouds from Gåsen Hut

|

| The cabins at Gåsen |

out

over the Helags and Sylarna mountain mastiffs. The evening before, the

hut had been socked in in the clouds and there were no views—we had

had no idea that Gåsen has such spectacular surroundings!

|

| Sunrise views of the Helags and Sylarna mastiffs from Gåsen |

From

the hut, we skied up to a pass where we sat on our packs in the warm

sunshine, enjoying the complete lack of wind and the clear, beautiful

mountain views.

|

| Views of the Helags and Sylarna mastiffs from the pass between Gåsen and Vålåstugorna |

We

continued to stop and take long breaks every couple of kilometers. At

lunch, Carl dug us a snow couch where we sat for an extended period in

the sun, enjoyed a leisurely lunch, and then even played a game of chess

while sipping cognac and eating chocolate-covered hazelnuts.

|

| Sun couch between Gåsen and Vålåstugorna |

When

we eventually got a bit chilled, we continued down the valley, but we

did stop for two more leisurely breaks before arriving at the hut at

Vålåstugorna.

|

| Valley between Gåsen and Vålåstugorna |

It

was a particularly magical day because we had skied through that same

valley in the fog last year. On the map, the valley looked like it

should be lined by dramatic mountains, but we didn’t get to see the

view. But this year, we had perfectly clear views and incredible

weather that let us stop and enjoy the beautiful scenery.

|

| Approach and cabin at Vålåstugorna |

Another particularly beautiful day was at Sylarna. We had had quick glimpses through the shifting clouds of the Sylarna mastiff’s dramatic form on our trip up over the pass to the Mountain Station,

|

| Between Helags and Sylarna |

but

the next day dawned sunny and clear and the full views of Sylarna were

even more awe-inspiring than expected—the Sylarna mountain mastiff is

unusually large, high and dramatic for this part of Sweden.

We

stayed two nights at Sylarna Mountain Station and on our “off” day, we

took a day trip skiing up into the mastiff. We went off the trail and

skied up and over a high pass where we had brilliant views of the Helags

mastiff, which had been mostly shrouded in clouds when we had been

staying and skiing at its foot.

|

| Our clearest view of Helags mastiff while staying and skiing at its foot |

Carl made us another sun couch and we were able to sit and eat a leisurely lunch with the incredible view.

The

mountainside was covered in what we believe to be arctic fox tracks;

while we didn’t see any foxes, we still felt awed to be in the presence

of the endangered animals. We skied back over the pass and then into a

bowl ringed by dramatic granite ridges. The afternoon sunlight was

magical and we skied very slowly, stopping often to enjoy the dramatic

panorama.

|

| Carl and I skiing in the Sylarna mountains |

Blåhammaren Mountain Station is known for its three-course gourmet candlelit dinners, and the reality of the experience lived up to our expectations. The food and wine were delicious and the atmosphere and comradery in the small, historic dining room, packed with skiers in long johns, was magical and unforgettable.

|

| Blåhammaren fjällstation |

Our last day was short, only 12 km between Blåhammaren and Storulvån Mountain Stations. We didn’t want our trip to be over, we weren’t ready to return to “civilization” and to end our vacation. Even though the weather wasn’t particularly sunny or warm, we stopped a lot, and Carl dug us two different snow couches which blocked the wind and allowed us to sit out for good periods of time. The middle part of the trail from Blåhammaren was quite downhill, and the weather was clear enough that we felt comfortable leaving the trail to play in the powder. We skied and skied downhill in the powder, picking a path that wasn’t too steep but that was steep enough to allow us to keep effortlessly and magically gliding through the snow. We could see the trail in the distance, so at the bottom of the mountain we were able to join back up with the trail with no problems.

|

| Between Blåhammaren and Storulvån fjällstationer |

Last year the snow was scarce and we even had to walk some portions on bare ground and our skis strapped to our backpacks, but this year, the snow was unusually deep and plentiful. It was so deep that drifts covered many of the hut windows and reached up and over the hut roofs. In some sections of trail, the snow was so deep that the red crosses marking the trail were completely buried. We were thankful that mountain rescue teams had been out and staked the empty sections with temporary poles so that there were no long gaps without trail markers. In a couple of places we came upon bridges where the entire river gorge was buried in snow up to the bridge cables.

|

| Lots of snow at Sylarna |

This year we changed our tactic and instead of taking advantage of the long weekend at Easter, we went ski touring a couple of weeks earlier in hopes of avoiding the Easter crowds. Our tactic was partly successful—there definitely weren’t the same hoards as at Easter, but the huts were surprisingly busy even in mid-March. A downside to going so early in the season was that the huts in Norway weren’t open yet. As we were skiing right at the border, we had originally planned to incorporate a couple of Norwegian huts into our itinerary but we ended up having to stay on the Swedish side. We got a bed in all of the huts and mountain stations except for Blåhammaren where the beds were full and we were given a mattress on the floor.

Unlike other areas of the Swedish mountains, this particular area of Jämtland has an unusually high proportion of “mountain stations” to “mountain cabins.” The mountain stations are fancier with electricity, gourmet meals, and hot showers. While I find it magical to end a trip with a comparatively luxurious stay at a mountain station, I don’t need or really want them throughout the majority of my trip. Too many mountain stations feels too civilized, attracts too many tourists, detracts from the landscape with snowmobile tracks for food deliveries and infinitely marching powerlines, and is expensive. I much prefer the comparatively simple mountain cabins with gas lighting, wood stove heating, and bunk rooms—they feel much more in keeping with the “wilds” outside.

During our trip, we experienced beautiful weather and we experienced worse weather, but nothing so bad that we were forced to stay inside or change our plans. However, conditions worsened once we reached the road at Storulvån Mountian Station. In hindsight, we should have taken the bus down to the main road the afternoon we arrived, but we didn’t realize that the weather would worsen so quickly. When we woke up the next morning, the small road up to the Mountain Station was closed. A snow plow tried to dig the road out, but the snow plow got stuck just 200 meters from the main road! The road ended up being closed from Saturday evening to Tuesday afternoon, but on Monday afternoon we were able to get a ride down the frozen river in a converted military snow tank which is now used to haul tourists and supplies around the mountains. We missed our train on Sunday and lost that money but thankfully there were last-minute tickets available when we finally got out, and we only had to unexpectedly miss one day of work. As usual, Carl and I are already dreaming and scheming about next year’s ski adventures....

TUESDAY, MARCH 06, 2018

Spur-of-the-Moment Cross-Country Weekend in Dalarna

Spur-of-the-Moment Cross-Country Weekend in Dalarna

Temperatures

in Stockholm had been below freezing for a couple of weeks, and there’s

been snow on the ground for a while, but sadly it had never bene enough

snow for cross-country skiing. Carl and I finally got fed up with yet

another disappointing winter in Stockholm and booked a rental car and a

very cheap hostel room for a spur-of-the-moment weekend of cross-country

skiing about 3 hours north of Stockholm in Dalarna.

We left Friday after work and were home Sunday evening so the trip was fairly short, but it was definitely long enough to exhaust ourselves! We skied nearly 20 kilometers on Saturday and nearly as far on Sunday—20 kilometers isn’t far for many cross-country skiers, but it’s about as far I can ski and still think it’s fun. Beyond 20 km, I’m generally physically exhausted and mentally done.

The boundary of skiable snow was actually only about an hour north of Stockholm, but we’ve had a specific nature reserve in mind for a while now, so it seemed like the perfect opportunity. We stayed in an adequate but unexciting hostel in Borlänge which is an uninspired small town. The hostel and town weren’t exciting, but Gyllbergen Nature Reserve was beautiful and definitely worth the trip for the skiing. The nature reserve is in the foothills of the mountains and is a small part of (one of?) the largest roadless area in the southern half of Sweden.

With a meter or a meter and a half of snow pack, the cross-country trails in Gyllbergen were first class. Because the nature reserve is in the foothills, some of the trails had a good bit of elevation gain and loss but the steep sections were relatively short and far between. The lower elevations featured a dense, mature forest

while

the upper elevations were more sparsely forested, a bit like a forest

near treeline, although the sparse forest is more due to historic

logging than Gyllbergen’s modest elevation of about 500m.

The nature reserve is speckled with simple wind shelters, and firewood is even provided for grilling. Next time we’re going to be sure to take newspaper and matches for a winter hotdog picnic! The wind shelters are smartly placed with pretty views and varying orientations so that while one shelter might be perfect for capturing winter morning sun, another shelter is perfect for enjoying a sunny lunch.

Carl and I enjoyed a gorgeous morning fika in the sunshine at a lake’s edge—even though temperatures were fairly cold at about -10 degrees C (14 degrees F), the sun and lack of wind made it possible to laze about outside for an extended period without getting chilled.

In addition to the more modern wind shelters, the nature reserve is also dotted with historic fäbodar, or summer cabins for the caretakers of grazing livestock. One historic building near the road is now electrically heated and is used as a warming cabin for skiers,

but the cabins farther out in the nature reserve retain their isolated character. I’m guessing they are still used as private summer cabins, but in winter they were quite desolate.

|

| So much snow! |

The forecast had been for grey days, but we totally lucked out with sunshine the first morning and a brilliantly sunny day all of Sunday. Some of the best “overcast” weather I’ve experienced, for sure. The sunshine, the glittering fluffy snow, the hilly terrain, the snow-covered lakes, the snow-adorned forest, and the varied ski trails coalesced into a beautiful weekend of wonderful cross-country skiing.

After we had exhausted ourselves for the day on Saturday afternoon, we had a bit of daylight left so decided to look at a couple of historic buildings in the area. Our first stop was at Torsångs Church which was built in the late 1300’s.

|

| Torsångs Church and bell tower |

The name of the church means “Thor’s Pasture” and alludes to the fact that the place was a sacred site long before Christianity arrived in the region. The church was most likely built over an older cult site.

|

| Left: A closer view of the church's gavel, the human figure is probably a Saint. Right: Incredibly detailed midieval ironwork on a door to one of the church's outbuildings. |

We

also took a look at Ornässtugan, a large log cabin built in the early

1500’s which featured prominently in Sweden’s history. After the

unwelcome Danish King invited 80 Swedish nobles including Gustav Vasa’s

father and then proceed to kill them all in the Stockholm Bloodbath,

Vasa was fighting to kick Denmark out of Sweden and to establish Sweden

as an independent monarchy. In order to do so, he travelled north to

Dalarna to enlist the help of the very powerful and very wealthy silver

and copper mine owners in the area. Without access to the wealth of the

mines or to the large population of the region, Vasa knew he wouldn’t

have the coffers or the manpower to fight off Denmark.

One of the mine owners lived at Ornäs, so Vasa visited to try to convince Pedersson to help his nation-building cause. Pedersson agreed and left the estate to enlist further help, but Pedersson’s wife knew that her husband was actually reporting to the Danish magistrate to arrest Vasa. She gave Vasa a horse, a sleigh, and a servant and helped him to escape the estate before Pedersson returned with the magistrate and a force of 20 men to arrest him.

Gustav Vasa was ultimately successful in kicking out the Danes (and Pedersson was hung for treason), and Vasa became modern Sweden’s first monarch. Ornässtugan has forever after been associated with Sweden’s saga of nation building and has been a museum since 1758. During the National Romantic period in the second half of the 1800’s, the cabin served as a main inspiration for National Romantic architecture and design, so it is important from an architectural perspective as well as from a historical point of view. The cabin is only open to visitors in the summertime, so we’ll have to return another time to see the interior.

Dalarna is a special region in Sweden in many ways, not least because its natural beauty (though much diminished by logging) and its unique folk culture are both so accessible and intertwined. The landscape wouldn’t be nearly as beautiful without the pervasive cultural layer, and the cultural layer wouldn’t be nearly as present without the relatively undisturbed landscape.

MONDAY, FEBRUARY 12, 2018

Serre Chevalier (Reprise)

Carl

and I are recently back from yes, yet another ski trip in the French

Alps. This year we returned with UCPA to Serre Chevalier, the beautiful

ski resort we visited in 2014 (see “Serre Chevalier on Two Skis”).

We returned to Serre Chevalier mostly because we’ve run out of UCPA

centers with double rooms, and are now rotating back through. This year

it was just the two of us without our usual group of friends. We

missed the usual suspects but enjoyed getting to know several really

welcoming and fun groups that I met through my groups.

I

write groups plural because I spent half the week with an All Mountain

off-piste (backcountry) group. I was learning a lot and improving, but

the pace was grueling and I was having trouble keeping up. I probably

didn’t improve as much as I could have because of the pace—I was

concentrating more on just getting down the mountain and keeping up with

the group to not get lost than on skiing with good technique. After

half a week of not quite keeping up, I moved down to a less taxing group

where I could work on my technique without feeling like I was holding

the whole group up.

Carl

skied as usual with a super-duper-expert off-piste group and had a

blast. He reports that his technique seems to be getting better and

better because he is able to ski really difficult slopes without feeling

exhausted at the bottom. I can’t wait to achieve the same level of

skills!

|

| Carl's group. For the record, my group did its share of walking uphill, too. |

Our

first ski day was on the slopes, and the snow was skiable but very hard

and crusty. If the resort had been busier, we probably would have been

skiing on pure ice. It snowed a good bit the next day which was

perfect for the next five days of (mostly) powdery off-piste skiing.

Four of the five off-piste days were brilliantly sunny with far-reaching

views of jagged ridge after jagged ridge. The scenery was stunning.

|

| Views from Serre Chevalier's groomed slopes. |

A

couple of days were very, very cold, approaching Tänndalen cold (see

“Snowy Holidays” below), but for the most part the temperatures were

perfect—cold enough to keep the snow fluffy but warm enough to enjoy

lunch in the sunshine. One day, my second and very awesome guide even

carried with her and grilled herb-rolled sausages for our picnic lunch!

It was probably the tastiest lunch ever.

We

solved the usual UCPA dilemma of not having enough hooks or hanging

space by rigging up our own drying line across the room. Perhaps it

wasn’t so savory to have sweaty long johns drying above us as we slept,

but at least everything was dry the following morning!

|

| The UCPA center is at the edge of the village of Villeneuve |

as

well as Briancon, a fairly large town and a UNESCO world heritage site

due to its historic walled town and series of fortifications built on

the ridges above the river.

|

| Briancon's walled town and fortifications from the ski slope. |

Even

though my backcountry skills didn’t improve to quite the level I was

hoping on this trip, I did learn a lot and I was definitely skiing

better at the end of the trip than when I started. I am already very

eager for next year’s off-piste trip!

Snowy Holidays

Over

Christmas and New Year’s, Carl and I spent two snowy weeks in the

mountains of Sweden. We rented a cabin outside of Tänndalen, a small

village near the Norwegian border. We chose the area after doing a lot

of research on historic snow data—aside from Riksgränsen which is above

the Arctic Circle and not even open in December and January due to the

darkness and the extreme temperatures, the Tänndalen region is Sweden’s

most snow-safe ski area. As it turns out, we didn’t need to worry this

year. Unlike the previous five Christmases, there was about a meter of

snow when we arrived in the mountains and it snowed at least another

meter during our two week stay.

The cabin was really too big for just two people after Eva left, but Carl and I did enjoy our evenings of solitude in front of the fireplace. Gordon seemed to love the fireplace just as much as we did, and he even stopped sleeping on our bed in order to snooze in the warmth of the dying embers.

|

| Random photo: cabins, frozen lake, and mountains. |

The area has three large-ish downhill ski resorts (large for Sweden anyway) and the world’s largest cross-country ski system with over 300 kilometers (!) of connected groomed trails. Needless to say, there was plenty to keep us occupied. We alternated most days with cross-country and downhill skiing, although when about two feet of snow fell in one day, we changed our plan and downhill skied in all that powder.

|

| Cross country trail map |

We

had beautiful views of the surrounding mountains and down into the

valley with its frozen lake. The pure joy of downhill skiing after a 9

month hiatus hit me hard after about two turns and I practically danced

down the slopes, hopping in my turns for joy. It was Christmas Eve, so

there weren’t many people out, and the slopes had just opened for the

season a couple days before, so they were soft and perfect. The

resort’s main black slope is crazy, crazy steep and while the definition

of a black slope is over 40 degrees, this slope averages 60

degrees. I pranced right down it repeatedly with no hesitation and no

problems, I was very proud of myself and the perfect skiing combined

with my feeling of accomplishment was just joyous.

The

runs are all on the same side of the same long mountain ridge, so you’d

expect them to be somewhat monotonous, but I was really gladly

surprised that most of the runs felt unique with their own twist on the

terrain. One side of Tänndalen is secured from avalanches, but it isn’t

groomed, so when it snowed two feet overnight, we of course headed to

that area first thing the next morning. The powder was gorgeously

fluffy, and we made new tracks high up on the mountain for most of the

morning.

|

| Stuck in powder |

By

the time we skied in Ramundsberget, the pistes were getting pretty icy,

and I sadly had trouble on some of the black runs. Well, I had trouble

on one run, and I really psyched myself out for most of the rest of the

day and didn’t recover my form or my confidence until late in the

afternoon. However, we had amazingly gorgeous weather that day, and the

beautiful views more than balanced out my negative feelings over my bad

form and psyche. When it became clear that staying on black slopes was

only going to make the day worse, we moved over to easier slopes and

had a blast.

Over the two weeks, I skied every day but two. The first day I stayed home because I came down with a cold. Luckily, the one day of rest was enough to cure me well enough to continue skiing for the rest of the trip.

|

| Sickbed view |

On the other non-ski day, we went on a gorgeous and fun snowshoeing adventure straight up the mountain from our cabin. The forecast was for low clouds, but as we climbed in elevation, the clouds cleared and the day became sunny and warm with beautiful views to the mountains above us and out to the valley below us. The sun made the snow sparkle and the ground and the trees seemed to be coated in diamonds.

|

| Tough going in all that powder on snowshoes |

|

| Easier going on an old ski tracks, racing to Andersborg waffle hut. |

|

| Andersborg waffle hut |

I was a bit worried about getting back to our cabin before dark, but once Carl reassured me that he had brought our headlamps just in case, I was able to slow down and enjoy the gorgeous sunset that enveloped the sky. As it turned out, we made it back to the cabin with a bit of daylight to spare.

|

| waddling uphill on cross country skis |

|

| Moss and snow covered trees |

|

| Old fäbodar at Hängvallen and Klinken |

and we had clear views of the surrounding ridges, urging us to keep going and to explore further. The trail continued to descend, and descend, and descend, and finally we decided that we really had to turn around so that we could get back before dark. We did get back to the car without too much ado, but we were completely exhausted by that point. The last couple of kilometers were fairly painful, and I just had to robotically make myself continue. That day, we broke our previous record of 22 kilometers by a long shot, skiing 28 kilometers within just a few hours. After that long day of cross country skiing, we didn’t really recover our energy for the rest of the trip.

|

| Old fäbodar at Bergvallen |

Hiking in the mountains of Sweden I’ve always been impressed by the emergency shelters that are spaced about halfway between each backcountry hut. Between the shelters and the huts, you’re rarely more than a couple hour’s walk from shelter and a fire. I’ve never been caught out in a situation where I’ve needed an emergency shelter in the Swedish mountains, but given the Arctic conditions, I’m glad to know they’re around.

Anyway, I was impressed that even the cross-country trails around Tänndalen are sprinkled with emergency shelters. All of the trails are meant as day trips, but even so, you never know when a blizzard is suddenly going to come and trap you. The emergency cabins provide shelter from the wind and snow as well as a dry place to sit, firewood, and a tiny wood-burning stove.

|

| Cross country emergency huts near Bergvallen and in Anåfjället |

One of the cross country trails we skied started out down in the valley. It was snowing lightly, but nothing to worry about. The trail climbed and climbed until it nearly reached treeline. At that point on the trail, the wind was so fierce that it was blowing the snow sideways and pelting it into our faces. Carl and I had to stop and put on our goggles to protect our eyes. It was very exposed up there and a bit scary, and I was very thankful to have an emergency shelter just a few kilometers away. But by the time we got back down to the shelter, the forest blocked most of the wind. In the end, we didn’t really need the shelter, but it was good to know it was there just in case.

|

| Carl and I on cross country ski trails |

One thing we learned while up in the mountains was that you can’t trust the forecasts for the area—they are often WAY off, forecasting complete cloud cover when the day turns out to be clear and sunny, forecasting temperatures of 21 degrees F when the temperatures fall to -8 degrees F. Not only are the forecasts completely off, but the “historical” weather data for the previous day was also completely incorrect. It turns out that the “historical” data is based on their computer-modelled forecast, so if the forecast was wrong, the weather service never updates to the actual data. Weird! Thank goodness the historic snow data seemed to be accurate!

Skiing in -22 degrees C or -8 degrees F was cold to say the least. It was the kind of skiing where you ski about 3 runs and then have to go inside for half an hour to thaw out your toes. The cold made Carl and I consider buying ski boot warmers despite their crazy high cost. Carl’s beard was coated in a thick layer of ice and globules of ice froze to my eyelashes.

One of the reasons we decided to stay in Sweden this Christmas was that we wanted to be able to vacation with our cat. We’ve never taken him on a road trip before, so we weren’t really sure how he would do in the car. Unfortunately, he was scared the entire eight hour drive. He was extremely well behaved and just snuggled in the passenger’s lap without trying to explore around the car, but he shook with fear the entire drive. We were hoping that he’d become accustomed to being in the car and wouldn’t be as scared during the ride home, but he was still quite shaky. Passing cars and the windshield wipers made him extra nervous. It’s too bad he was too scared to enjoy the beautiful landscape on the drive.

|

| On the drive back home to Stockholm |

TUESDAY, NOVEMBER 14, 2017

Island Weekend

Last

weekend, Carl’s Aunt Eva invited us out to her cabin on Svartlöga, an

island in the northern part of the Stockholm Archipelago. We’ve been

out there with her before, see my post “Three Weekends in the

Archipelago.”

(http://walkingstockholm.blogspot.se/p/travels-continued-7.html ) So

late in the season, there’s no Friday evening boat so we arrived late

Saturday afternoon and had to leave again mid-afternoon on Sunday. It

was a short but lovely weekend.

Fall

colors had peaked a couple of weeks before our island weekend, but

there was still some glowing fall foliage out our window as we read and

sipped coffee on the boat. But by the time we got out to the more

exposed Svartlöga, all of the trees were bare.

we

proceeded to cook up a four course meal on the wood-fired iron stove.

First, Eva roasted slices of butternut squash and topped them with

chevre and pomegranate seeds. Then Carl fried up some of our newly

picked mushrooms in butter and made mushroom sandwiches. Carl and I

then made cheese polenta topped by fried mushrooms. Dessert was an

array of delicious cheeses, recommended to Eva by her favorite

cheese-store employee. We had had plans of roasting apples as a second

dessert, but none of us had any room to even contemplate a fifth

course. Eva even brought three perfectly paired wines to accompany our

meal. The candle-lit and woodstove-heated evening in Eva’s little

island cabin was exceptionally cozy.

|

| Cleaning and frying mushrooms by candlelight |

We

returned to the cabin for lunch and a bit of cleaning up, and then we

said goodbye to Eva whose boat left a bit earlier than ours. Before we

had to walk over to the ferry dock, Carl and I managed to pick another

kilo or two of mushrooms. Given how expensive gourmet forest mushrooms

are, we’re pretty sure that we recouped the cost of our ferry tickets

just by picking mushrooms for a couple of hours!

|

| The grey, somewhat dreary weather and bare trees did not detract from the island's beauty. |

MONDAY, OCTOBER 16, 2017

A Weekend in Århus, or Aarhus

Carl

and I met up with our friends Susanna and Johannes and their daughter

Agnes in Aarhus, Denmark last weekend. The focus of the weekend was

hanging out and catching up, but we did manage to squeeze in some sight

seeing during the pauses in our chattering.

Århus is really hot on the contemporary architecture scene right now, and we saw one hot-off-the-press project, Your Rainbow Panorama, which is an addition atop the local contemporary art museum. Olafur Eliasson designed a 360 degree viewing platform looking out over the city. The donut is perched on top of the museum in such a way that when walking through it, you feel like you’re hovering inside a rainbow because you don’t sense any contact with the museum’s roof or the ground. The colored glass shifts from blue to red to yellow to green to purple as you walk around the loop. I wasn’t terribly excited about the donut’s appearance from afar, but I loved the experience from the inside. Aside from its hovering construction, it really is a simple project, but super effective.

Århus is really hot on the contemporary architecture scene right now, and we saw one hot-off-the-press project, Your Rainbow Panorama, which is an addition atop the local contemporary art museum. Olafur Eliasson designed a 360 degree viewing platform looking out over the city. The donut is perched on top of the museum in such a way that when walking through it, you feel like you’re hovering inside a rainbow because you don’t sense any contact with the museum’s roof or the ground. The colored glass shifts from blue to red to yellow to green to purple as you walk around the loop. I wasn’t terribly excited about the donut’s appearance from afar, but I loved the experience from the inside. Aside from its hovering construction, it really is a simple project, but super effective.

|

| Your Rainbow Panorama from afar and from the museum's roof terrace |

In contrast, we spent most of the second day walking through Århus’s open air museum and its collection of historic buildings. I’ve always been a sucker for open air museums with employees in period costume, but Århus’s was even cuter than most. The buildings are uber-picturesquely grouped along a canal and in village blocks around squares. Just about every turn was a “it’s just so cute” moment. The museum makes it clear that life back in history wasn’t so rosy, but the village-scape is so picturesque that it’s hard not to idealize the time period.

|

| Den Gamle By |

Besides being a contemporary architecture powerhouse, Århus was a lovely little city and its livability seems to belie its tininess. Århus is Denmark’s second largest city, but its population is only 325,000, many of whom are students at the university. Its petite size and relatively high, city-like density means that the town is very walkable and everything is within easy reach. But despite its petite size, the city features world-class museums, cultural institutions, and a “culture house” / central library with an impressive array of activities and services.

Thank you Susanna and Johannes for a great weekend!

|

| There's probably only another weekend of fall in the region before pre-winter sets in. |

Celebrating Fall on Gotland

Last weekend, Carl and I celebrated the beginning of my favorite season by taking the ferry to the island of Gotland and spending a lovely fall weekend on the island. We stayed at Carl’s parents’ house although they were away on vacation and explored two distinct areas during the days. Autumn was in full swing with gorgeous, relatively warm and sunny days, chilly nights, and leaves that were just beginning to turn yellow to match Gotland’s golden light.

After arriving with the ferry, we picked up our rental car in a parking lot near the ferry terminal—in true Gotland relaxedness, there were no attendants and the keys were waiting for us in the unlocked car which we found in the lot because the rental company had emailed us the license plate number. We swung by the grocery store and then drove the 10 km to Carl’s parents’ house where we crashed into bed almost immediately after arriving.

The next day we got up early and returned to Fårö, another smaller island just off Gotland’s northern tip. We had spent a day exploring the island with Carl’s parents in the early summer (see Gotland, Sweden's Provence below) but wanted to return to look more methodically and slowly at the quaint buildings. Like the mainland of Gotland, very little has changed on Fårö since the middle ages. Despite a modern onslaught of summer residents, the island has retained much of its medieval character and pattern of land use. Fårö is still dotted with thatched sheep sheds (often still in use),

windmills (mostly unused today),

and stone farmhouses which with their adjacent barns and outbuildings form an enclosed courtyard (still in use either as farmsteads or as summer residences).

As if the thatched sheds, windmills, and historic stone farmhouses weren’t picturesque enough, the island’s landscape is still divided into fields by particularly scenic stone walls.

The main road still partly follows its historic route, but in some places the road has been straightened and skips extra-scenic villages. We spent half the day tracing the road’s historic route and fell in love with some of the small villages that have been bi-passed.

The relatively low intensity of development over the millennia on the island means that many traces of pre-historic settlement are still visible. For example, a presumably bronze-aged stone wall has mostly disintegrated as stones were relocated to newer structures on the property, but the wall’s path is still visible because the larger, difficult-to-move stones remain in their original location. We also took a short evening hike by several iron-age grave mounds. One was particularly interesting because it had a double ring of larger stones which are still obvious today.

We ate lunch and spent a couple of hours lounging in the sun on the beach at Helgumannens fiskeläge, a small “village” or camp of fishing huts and storage sheds at the water’s edge. Most farms, even in the interior of the island, historically had fishing rights and subsequently the right to boat storage and a fishing hut at the water’s edge. The farmers typically fished together in teams and therefore built their huts on the same stretch of beach at their assigned fishing camp. These huts are still used today, although the fishing is more on a leisure than subsistence basis. In the summer, the huts’ owners hang out and picnic at the fishing camp, only sometimes in conjunction with taking their boats out for fishing. The fishing camps are a historical phenomenon which have molded social interactions into the modern era (a lot like the historic church town in Luleå, see my post “Luleå Gamla Kyrkstad (Luleå Old Church Town)” below).

The fishing camp at Helgumannen is particularly scenic because the cluster of huts is relatively large and because the various huts are built of different materials varying from stone to wood, and because the huts are slightly different sizes with slightly different roof forms. Even the wooden huts are varied in appearance because the wood is treated in different ways, giving the huts different shades of color.

At sunset, we took the car ferry back to mainland Gotland and drove back to the house where we relaxed in front of the wood stove with a bottle of wine. Eventually we prepared a gourmet dinner and then fell exhausted into bed.

We got up early again the next day and cleaned up the house and packed up our rental car. This time, we stayed on mainland Gotland and drove a good ways south to explore one corner of the island known as Östergarn. We stopped on the way at Källunge Church which has quite a distinct form. The original stone church was modest in size and Romanesque in design. By the 1300’s, it was meek and old fashioned, so the parish started to rebuild the church into a much showier building with a larger, Gothic nave. In the middle of the 1300’s, Gotland’s economy completely collapsed with the arrival of the plague, and the parish was unable to complete the church’s expansion. Instead, the partly finished nave was connected to the much smaller original Romanesque church and tower, giving the church its odd form. The church is a physical manifestation of the sudden halting of Gotland’s economy in the 14th century.

Our main destination of the day was Torsburgen fornborg, or Torsburg pre-historic fortress. There are about a thousand pre-historic fortresses in Sweden, and more sprinkled throughout northern Europe, but Torsburg is among the largest with a circumference of about five kilometers (three miles!). The fortress is built atop a natural height of about 100 feet, the only major rise on this part of Gotland, with limestone cliffs creating a natural defensive wall around more than half of the plateau.

|

| View from the top of the fortress out over the flat landscape |

Where the plateau slopes down more gradually, iron-age Gotlanders built a massive dry-stacked limestone wall to complete the plateau’s enclosure. This wall is two kilometers long, 7 meters (23 feet) tall, and 20 meters (65 feet) wide. While the wall now appears to be a heap of stones, several sections of orderly stacked stones remain, showing that the entire wall was once a careful construction. It is believed that a wooden palisade provided further height and protection around the circumference of the fortress. This wall was in other words a massive undertaking which would have required a centralized, organized society, the likes of which isn’t really otherwise documented in Sweden’s pre-history. Torsburgen fortress is one of many clues indicating that iron-age Sweden was much more developed than otherwise thought.

While most pre-historic fortresses in Sweden are sized to hold a clan, Torsburgen is so large that it is thought to have been able to protect the entire population of Gotland. It isn’t known what the threat was, or what direction it was expected to come from. Being a bit inland, the fortress didn’t have a view of the sea, but a chain of smaller fortresses visually connect Torsburgen to the water’s edge and a system of fire signals would have provided advance warning of an attack from the sea.

|

| Stacked stones at Torsburgen |

Carl and I are perplexed by Torsburgen. Even if the fortress was large enough to defend the island’s entire population, the island is too large for it to have been effective. Traveling from one tip of the island to the fortress would have taken at least a day on horseback on good roads, if not longer. By that time, an attack would already be in full force. Additionally, even if the natural cliffs and beefy stone walls were hard to scale, hundreds of people would have been needed to defend the entire five kilometer circumference—it just doesn’t seem practical to defend such a large area with the era’s limited technology. There is very little archeological trace of activity within the fortress, so it doesn’t seem like a defensive force was permanently settled inside. And while there were iron-age farms in the surrounding areas, it doesn’t seem like there was a large enough, readily available source of defensive manpower in the immediate surroundings to defend the fortress at a moment’s notice. Despite the fortress’s impressive scale and the high level of sophistication that the society must have achieved in order to build such a structure, researchers really have no idea why it was built or how it was used.

Carl and walked halfway around the circumference of the fortress, ate lunch on top of the wall, and then cut across the middle back toward the car. Walking around and through it gave us a sense of the fortress’s scale—the fortress is truly enormous and the wall is even visible in satellite photos. Along the way, we found a “grove” of funnel chanterelles so we stopped to pick the mushrooms. Within half an hour we had collected about two liters of them! They became delicious mushroom sandwiches later in the week.

At the bottom of the fortress, a picturesque collection of eighteenth century farms (sadly, we couldn’t get close enough to take good photos of the beautiful buildings, but the surroundings are extremely atmospheric) is the starting point of a cultural walking trail through an iron-age farming settlement which would have been roughly simultaneous with the hilltop fortress.

|

| Historic farm still in use today for raising sheep |

|

| Left: The outline of the foundation of an iron-age house. Right: mysterious grooves in the bedrock, possibly from sword sharpening. |

After Torsburgen and the iron-age farm settlement, we stopped at another medieval church in the village of Gammelgarn. This church is interesting because of the adjacent 15 meter tall defensive tower from the 1100’s. By the 1100’s, Gotland had built up incredible wealth and became a prime victim for pirate attacks. In defense, Gotlanders built a series of defensive towers to store their valuable exotic goods. The need for defense was apparently not just limited to the iron age! Only a few of these towers are still standing on the island today.

Our last stop before heading to the ferry back to Stockholm was another scenic fishing camp, Grynge fiskeläge. At Grynge, all of the huts were built of stone which was covered by layers of plaster in various stages of disintegration. Even today, most of the sheds have wooden plank roofs, and there are still flimsy wooden structures for drying fishing nets outside the huts.

Our weekend on Gotland was short but packed with incredible sights and landscapes. It’s such a magical island; Carl and I plot about one day moving there. (We also plot about moving to the Swedish mountains, or to the Alps, or maybe to Italy...) But in the mean time, we are incredibly lucky to have a base for island explorations! Thank you Ylva and Anders!

Work Study Trip to Basel, Switzerland

In past years I’ve traveled with my office to Lisbon and to Lyon to look at architecture, this year it was Basel. I’ve been operating on the philosophy of choosing my work study trip destinations by choosing the destination on offer that Carl and I are least likely to travel to by ourselves. While Carl and I are likely to return to Switzerland for more skiing and for summer hiking, and even to take a road trip to visit Switzerland’s castles and small villages and vineyards and thermal baths, Basel would probably never have popped up on our itinerary as it is short on traditional tourist sights, far from the mountains, and doesn’t even have a major airport.

|

| Basel |

However, as a contemporary architecture-based destination, Basel was extraordinary. We visited two campuses loaded with starchitect (star architect) buildings, and a stroll down a regular city street reveals one Herzog & de Meuron building after the next, not to mention surprise jewels of buildings which pop up every now and then.

|

| random: two double-duty radiators |

One of our first stops was to the Novartis Campus. Novartis is a relatively new pharmaceutical company that was having difficulty attracting leading researchers. After the ivy-covered campuses of Harvard and Yale, the original campus of ugly 70’s high-rise office buildings was not all that enticing. Novartis’ major successful strategy to recruit key researchers was to create an appealing campus that was impossible to say no to. Novartis has subsequently hired just about every major starchitect on the planet to design one building each, and the result has been successful—Novartis is now the second largest pharmaceutical company in the world.

I personally would have designed the Novartis campus differently—I think the urban planning was uncreative and a bit stifling. It is too rigid to allow the buildings to interact with the planned outdoor spaces. However, both the architecture and the landscape architecture were stunning. Buidings by Yoshi Taniguchi, Rafael Moneo, Frank Gehry, David Chipperfield, Tadao Ando, Diener & Diener, Fumihiko Maki, Herzog & de Meuron, and Alvaro Siza are punctuated by art by the likes of Serra and beautifully designed parks, whose landscape architects are strangely not listed on Novartis’s website. The architecture is minimal, clean, and precise, just as you might expect from a Swiss pharmaceutical company.

Security on the Novartis campus is stunningly rigid—to even get signed up for the tour, we had to send in our passports and they did a background check on each of us. Once on site, we had to give up our passports during our visit. Not only did we have a tour guide, but we were also followed by two security guards for the duration of our 2 hour tour. We were not allowed to take a single photo. We saw most buildings from the outside, but we did get to go into one research building. To get in, you have to go through a security lock—in one door, wait for it to close behind you, then the next door opens. Vice versa on the way out.

The second campus that we visited was Vitra, which was technically just across the border in Germany. Vitra is the European equivalent to Herman Miller with licenses to produce famous design furniture such as Eames and Aalto. Originally, the Vitra campus was a ho-hum industrial zone, but a major fire at the beginning of the 1980’s gave the company the opportunity to re-think their approach. As producers of high-quality, high-design furniture, it is only fitting that the company be housed in high-quality, high-design buildings. Grimshaw and Gehry

|

| Gehry's museum and back entrance to an industrial workshop |

|

| Hadid's firestation |

|

| Siza's industrial workshop |

|

| Herzog & de Meuron's museum |

|

| SANAA's idustrial workshop |

In addition to an architectural tour of the campus, we also visited Vitra’s showroom where their furniture is fancifully placed into different settings. While it’s not a museum, the showroom is a who’s who of 20th century furniture design and a very good education in modern industrial design.

|

| Herzog & de Meuron's showroom |

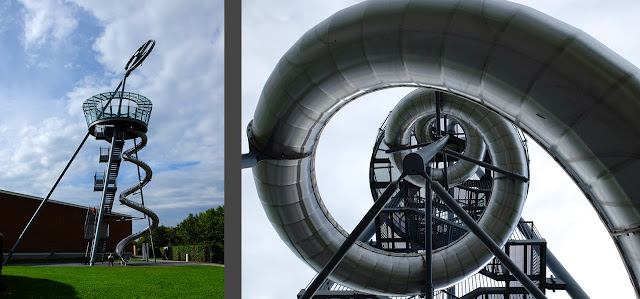

Additional projects of interest that we stopped by include Herzog & de Meuron’s conference center and transport hub “the donut,”

Christ & Gantenbein’s art museum addition,

Hermann Baur’s exhibition space at Basel’s design school,

and a recent addition to the Swiss National Museum (in Zurich) by Christ & Gantenbein.

Not only were our days devoted to architecture, but we also dined in architecture. Our first evening, we ate at Viaduct, a restaurant built under a railroad viaduct. The restaurant is one of many reclaimed spaces in the district, each built in its own arch. Our next evening was a fancy dinner in the Herzog & de Meuron designed Volkshaus. The third evening was a sharp contrast as we ate in a touristy traditional beer hall complete with waiters dressed in dirndls and lederhosen.

The long weekend was intense and exhausting, but also inspiring—seldom does one see so much capital A architecture in such a short time span!

|

| Aweseome slide on Vitra's campus--a bit of play amidst all that architecture! |

All the above images are my own except for

Volkhaus: https://volkshaus-basel.ch/en/brasserie/

Novartis: http://campus.novartis.com/#/browsecontent/basel/buildingmap

A Canal, a Wedding, and a Palace

Some

friends of ours invited us to their wedding which was celebrated on the

coast about an hour and a half south of Stockholm. While we were at

it, Carl and I decided to make the trip into a weekend road trip to see

some of the things that have been on our Sweden list for too long. Our

first stop was the charming little town of Trosa which is situated along

a short canal leading to the coast. I never did find out where the

town’s name came from, as literally translated from modern Swedish it

means “underpant” (singular, not plural). I am fairly certain that the

town’s name, which is at least 500 years old, did not stem from the love

of undergarments.

In any case, Trosa was an important town in the middle ages due to herring fishing, but like so much of Sweden, it was affected by the rising of the land and the river connecting the town to the Baltic Sea became too shallow. The town was moved in the 1600’s to the coast, but was later burned down by the Russians who set fire to most of Sweden’s Baltic coast in the early 18th century. Trosa rebuilt again in the mid-1700’s but the herring were soon thereafter fished out. The town was dying a certain death until the town reinvented itself in the mid-1800’s as a bathing/health resort for wealthy Stockholmers who took the steamboat down from the city. At this point the creek was expanded into today’s scenic canal as a conscious way to beautify the town and make it attractive to tourists, and Victorian era pensions with bay windows and lots of gingerbread trim were built along the canal. Today, the bath houses are long gone but the tourist industry is still strong. It was fairly quiet while we were there at the end of August, but the town is apparently full booked through the summer vacation season.

|

| Trosa's canal |

|

| Trosa's canalside houses range from huge and show-offy to small and vernacular |

|

| Tureholms slott was burned down in 1719 by the Russians. It was rebuilt in the mid 1700's by architect Carl Hårleman. |

The wedding was a bit outside of town in a nature reserve—it was fun walking down a forest path in fancy wedding clothes. The ceremony was held on a small platform overlooking the water and the archipelago, and the bride and groom totally lucked out with beautiful weather. After the ceremony, the simple but fun reception of dinner and dancing was held near the marina. We ate, chatted, danced, and celebrated until almost two in the morning, at which point we were glad to have a short walk to our mini cabin at the marina.

|

| Tullgarn Palace in the 1600's, considered way too old fashioned in the 1700's. |

Vast pleasure gardens replaced the old farming fields and barns that had once surrounded the house.

|

| Tullgarn Palace is out on a peninsula jutting into the Baltic. |

|

| Originally, this was the backside of the palace as it was most commonly approached by water. However, today, the front door is on this land side of the building. |

|

| Historically, visitors approached the palace from the water and entered through this courtyard. |

|

| Tullgarn's orangery |

WEDNESDAY, SEPTEMBER 27, 2017

Luleå Gamla Kyrkstad (Luleå Old Church Town)

Carl and I have been adding sites to our “Sweden To-See” map since we moved here. Even though we do a better job than most to get out and see things off the beaten path, we add far more sites than we manage to cross off every year. Some of the sights are so far off the beaten path that we might never get to them. The old church town outside of Luleå was one such place—although Luleå is one of the main cities of Northern Sweden, we are unlikely to ever have a reason to swing by. So while we were hiking “nearby” in Sarek (see my post just below), we decided to make a point of going home through Luleå. “Nearby” is a bit of a stretch since Sarek and Luleå are about 6 hours apart by bus and then train, but in relative terms we were next door.

I’m glad that we made the extra effort to swing by Luleå, because I found the history of the old church town fascinating. First of all, while Sami have been living this far north for millennia, this area of Sweden wasn’t colonized by “Swedes” until the mid-1300’s. It was a conscious colonization, and the original purpose wasn’t to Christianize the Sami as I first suspected. Instead, Sweden and Russia were bickering about the border (Finland was then under Russian rule), so Sweden decided to colonize that part of the vast northern lands in order to stake a claim before Russia got to it. The 14th century version of planting a flag was to build a church, so a church was built on an island where the Luleå river empties into the Baltic Sea even before there was a Christian population to attend the church. Swedes were then incentivized to relocate northwards by free land a ten year tax exemption.

The Christian population of Norrland remained small and spread out for several centuries. Although Luleå’s parish was in fact bigger than Holland, Belgium, and Luxembourg combined, the population was pretty minimal. Even so, regular church attendance was required by Swedish law, so the church was well attended. Luckily, weekly attendance was only required by those living within a 10 kilometer radius of the church. Within 20km, you had to attend every other week. Every additional 10 km gave you another pass; those living the farthest out were only required to attend church for the holiest feast days. Their journey to church took a week, and after church, the journey home took another week.

Given the long distances that parishioners traveled to church, it was only practical that they spend the night in Luleå before and after mass. Parishioners were granted the right to build a small cabin on the church’s property, but they were only allowed to spend the night in conjunction with attending church. No planning was involved in deciding where the cabins were to be built; people built themselves a small cabin wherever they found an open spot. For the most part, parishioners built a cabin on the road leading from the church out to their part of the country, and neighbors at home tended to build beside each other at the church. Narrow grassy lanes meandered between the cabins, and outhouses and small, individual stables made the spaces between cabins even more crowded than today. Luleå’s old church town is an excellent example of an organic, medieval town structure.

Because attending church was the one social event in their lives, parishioners generally welcomed church weekends. Markets were also held during the weekend, so attending church was also the main outlet for parishioners to sell or acquire goods. Church weekends provided a lot of free time—back on the farm life was just work work work but at the church town, maintenance of the small cabins required limited investments of time. Marriage partners were found during the church weekends, and church weekends ensured that brides would continue to see their families despite moving long distances with their grooms. Church weekends were the main social fabric holding Norrland’s society together.

I was also fascinated by the 19th century tradition of nattfrieri or “night proposal.” There was a population boom in the mid 1800’s due to the modernization of farming practices and suddenly, the family cabins were too small to house everyone. Instead of building more cabins, the solution was to split up the weekends between the older and younger generations. Certain holidays were “old people weekends” and other holidays were “young people weekends.” On young people weekends, the girls were given keys to their family’s cabins, but the boys were left keyless. They were to wander the lanes, charming the girls until they were secretly invited in to spend the night. After dark, the boys returned and were let into the cabin, where they slept next to the girl. The girls slept under the covers and the boys were required to sleep on top of the covers. What an intriguing way to “try on” marriage without any commitment! I’m sure that a number of pregnancies resulted from the night proposals, but it seems that the number of sisters and cousins that must have also shared the one room cabins would have kept most of the teenagers on the correct side of the covers.

Luleå’s old church town is a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The nearly untouched, organic medieval town plan is one reason, as is the fact that Sweden’s other church towns have not been well preserved so Luleå is the one remaining example of a once common phenomenon. But the main reason for the UNESCO listing is that the tradition of church weekends has an unmatched continuity; the tradition began in the 1300’s and the cabins are STILL USED IN THE SAME WAY TODAY! It’s truly incredible that the tradition remains intact after almost 700 years, even today despite all of the modernity that has changed just about everything in our society. If the church town had only been about religion, the tradition never would have lasted given Sweden’s lukewarm commitment to religion these days. But because the church town was also about socializing, about enjoying free time, about finding a partner, and about catching up with old friends and neighbors, the church weekend custom is timeless.

Cabins can be bought and sold, but many of them are still passed down through the generations. Some of the cabins have been passed down in the same family for 500 years! Given their cuteness, the church town’s history, and the popularity of the cabins, it’s actually relatively cheap to buy a cabin. But the purchase comes with a very expensive maintenance agreement—uncared for cabins revert to be property of the church, and all maintenance must be carried out with traditional materials and methods. Cabins are required to be painted barn red with white trim and shutters.

It’s impossible to date the cabins because the timbers were usually recycled in several different farm buildings before being dragged behind a sleigh to serve as a church cabin. As different timbers rotted, newer timbers were brought in to replace them.

It’s generally assumed that most of the cabins date back to at least the 1500’s but some are probably older and some are definitely newer. I was intrigued to see that the detailing of the doors, window frames, and shutters was predominantly from the 1700’s in a chunky version of the sleek Gustavian Neo-Classicism.

The “modern” city of Luleå was founded in the 1600’s when the harbor at the church town became too shallow. The new town is situated at the mouth of the river as it empties into the Baltic Sea so it is surrounded by water. It is laid out in a regular grid pattern and is quite walkable with an active commercial district and a central park. Attractive historic wooden buildings are mixed in modern structures, most of which are architecturally hideous. Modern Luleå is definitely not Sweden’s most scenic town, but it seems pleasant and livable with a relaxed pace. I don’t feel a need to return to Luleå, but I did find the historic church town intriguing. Plus, I always do love crossing things off my list!

WEDNESDAY, AUGUST 16, 2017

Three Weeks in Sweden's Arctic Mountain Wilderness Sarek

Carl and I are recently back from an epic three weeks in Sweden’s artic mountain wilderness, Sarek National Park.

Three weeks living in a tent is an adventure by any account, but crossing Sarek is adventure on a whole new level. Unlike national parks in the US, Sarek is completely undeveloped. It is even wilder than a national wilderness area in the US. Sarek has no roads and no huts, and two areas of Sarek compete for Sweden’s remotest point, farthest from any road. Sarek has no marked trails, no signs, and no bridges. There is certainly no cell coverage in the area. There are very few hikers in Sarek, and helicopter transport is not permitted. Sarek is above the Artic Circle and weather can quickly turn nasty; Sarek gets more precipitation than anywhere else in Sweden—2 meters or 6 ½ feet of rain every year. All navigation is up to the hiker, as is finding safe fords across rivers.

There are exceptions to the rules above. While there are no marked trails, some trails do exist in the most popular valleys where one hiker generally follows the same route as the next. However, these trails tend to die out as soon as the terrain gets rough, for example through bogs, so when you would really want a trail to follow, it disappears. There is one safety shelter with an emergency telephone in the middle of the park, located near the park’s one bridge which is at a critical junction of impossible to cross rivers. These amenities have come about due to the Sami reindeer herders who have been herding reindeer on the land for millennia—the bridge exists to aid in reindeer herding but as a side effect, it makes a through-hike from one end of Sarek to the other possible. The herding communities also have the right to small, rustic cabins in several locations in the park, but these are locked and unavailable to hikers. Sami herders also have the right to fly in and out on helicopters, and I believe that helicopters are also allowed to be used for emergency rescue operations.

Carl and I had attempted to cross Sarek a few years ago (see “Hundreds of Reindeer, 269 Kilometers, 24 Days, 1 Fox, and 0 Sunsets in Lappland, Part 2: Sarek National Park”) but turned around due to tiredness (we had already been hiking for two weeks) and due to a week of relentless rain. This time, we decided to focus our energy only on Sarek—we’d start out with two weeks of food so that we could either wait out the rain if the weather was bad or climb up into side valleys if the weather was good. This time we were successful in our through hike. The weather wasn’t perfect so we didn’t have as many side-hiking opportunities as we had hoped, but we did make it into a few extra valleys that we had been hoping to see.

The trip started with six days of rain. Some days the rain was relentless and some days it drizzled on and off. Sometimes we were completely fogged in with no view whatsoever, but we did have some mountain and valley views for a good part of our rainy week. The temperature never varied much above or below 5 degrees C (40F) during this period—the typical dream summer vacation spent in thick down jackets, long underwear, and rain/wind gear!

Other than the dramatic scenery, one of the main highlights of the trip were all the reindeer. We have loved seeing reindeer on previous hikes and ski tours, but this time we had the opportunity to experience more aspects of their behavior. One evening, we were lying in the tent hiding from the rain and we heard loud grunting noises. It sounded almost like a boar, but I doubted that there were boars that far above tree line. Besides, the grunting seemed to be coming from a rather large animal. Suddenly we got nervous that there was a grizzly bear outside of our tent—they do roam Sarek but are rarely seen and are never dangerous to humans. When we opened up the rain fly to look, we saw that it was a male reindeer grazing nearby. After that evening, whenever we came across herds of reindeer, we noticed that they communicate verbally with each other through various grunting sounds. A couple of times, large male reindeer with impressive racks directed warning grunts at us because we were too close to the herd. While the rest of the herd walked away, the male protector confronted us, grunting and pawing at the ground.

A couple of other special moments involved reindeer crossing rivers. The first time we saw them cross a river, we ourselves were looking for a safe ford across a wide, deep river. We saw several reindeer cross a good bit farther upstream and figured that they would know where the safe fords would be. Sure enough, when we got to their crossing, we saw that it must have been a very popular reindeer ford because there was a worn trail in and out of the river on both banks. We used their crossing and while it was our deepest ford of the trip with water up to our hips, the flow was manageable and we safely made it to the other side. Several other times we watched groups of reindeer cross deep rivers, but those times, the rivers were so deep that the reindeer were forced to swim. One river was flowing very fast and the reindeer climbed up out of the river a good ways downstream from where they had started. Even so, they all made it successfully across, even the reindeer that hesitated a long time before plunging in. After swimming, the reindeer shook the water out of their fur like dogs. The reindeer that hesitated to swim often shook themselves off repeatedly, like they were shuddering from the memory of the cold, terrifying swim.

The herds generally grazed lazily, moving as groups across the meadows and valleys. But on the warmer, sunny days, the weather was just too hot for these artic creatures. On sunny days, the herds lazed about on snow patches, snoozing, sometimes rolling over to cool off their backs. When they were snoozing on patches of snow, they were more reluctant to move off than when we approached on cooler days. Then, they often skedaddled away before we got very close at all.

One time, we were sitting on a ridge which dropped steeply into a creek. A very large herd of reindeer with maybe 300 individuals were rambling across the area, grazing as they went. Because of the steepness of the ridge, they couldn’t see us sitting above the creek. As they rose up out of the creek, the reindeer became startled at our presence and began trotting away from us. It was an enchanted moment being so close to so many running reindeer. I wouldn’t quite call it a stampede, but it was close.

The last time we were in Sarek, I was plagued by leaky boots. Our tent was a bit leaky, too. This time, we had a newer tent and my new boots stayed wonderfully dry.

Even so, with all the rain we had, our clothes still got pretty wet. It was a constant battle to dry out our clothes, socks, and rain gear as much as possible, and every remotely sunny and dry moment we had at camp, we had clothes hanging out on a line strung between our hiking poles and anchored by snow shoes and water bladders.

Even when it was raining, we tried to dry out socks by putting them in the space between our mesh inner tent and the rain fly. This method worked well when the temperatures were warmer but on the colder days, nothing dried at all.

Three weeks is a long time to hike without doing laundry. My clothing supply consisted of three pairs of socks, two pairs of hiking pants, six pairs of underwear, two hiking shirts, two bras, a hiking fleece, a pair of warm socks for camp, a long john top and bottom for sleeping, a hat, a pair of gloves, and a big down jacket. We had planned to wash our clothes by hand when we emerged from Sarek to buy supplies at Aktse cabin (2 day’s walk from the nearest road), but the cabin didn’t have a drying room like most of Sweden’s other mountain cabins. Given the humid weather, we didn’t think we’d ever be able to get our stuff dry, so we didn’t bother washing at the cabin. Toward the end of our trip, we were getting desperate. The sun was shining, so we washed a couple of pairs of underwear and some socks in a stream. A few minutes after we hung them on the line to dry, more clouds closed in and it rained for the next two days. So much for trying to clean our clothes—they ended up getting mildewed and were more disgusting than before we had washed them.

We were a bit more successful in cleaning ourselves. We bathed in streams with biodegradable soap on four occasions. Three of the baths were extremely cold—we were bathing in water that was only a few meters downstream from snow fields or glaciers.

In preparation for our trip, Carl experimented a lot with drying food at home. His experiments were very successful and during the first two weeks, we enjoyed the tasty, nutritious meals that he had dried including spaghetti with meat sauce, beef and vegetable stew, sweet potato soup with chicken, Asian noodles with veggies and chicken, and mashed potatoes with smoked pork. For lunch, we alternated between brie and salami on crackers. Breakfast was either oatmeal or granola with powdered milk.

We carried two weeks of food with us and planned to be at Aktse cabin before we starved. A quick through-hike of Sarek takes a week, but we gave ourselves 14 days so that we would have time to sit out bad weather, sit and enjoy the scenery, and do day hikes up side valleys. We strolled down to Aktse cabin on day 14 and resupplied with much less exciting food—oatmeal with no sugar for breakfast, squeeze tube cheese on hard tack bread, and tasteless, textureless freeze-dried dinners. We certainly didn’t starve during our third week on the trail, but by the end of the week, we were more than ready for real food.

There are two north-south trails on either side of the park that make convenient approaches and exits from Sarek. We followed the very wet Padjelantaleden through Padjelanta National Park for a day before turning into the park. On the other side, we used Kungsleden (The King’s Trail) as a quick thoroughfare out of the park.

It ended up being good that we had a lot of extra time to cross Sarek because our original path through Guohpervagge Valley turned out to be impossible. As I mentioned above, there are no bridges and hikers have to find their own places to cross rivers. We had already crossed many rivers by the time we got to one that was just too deep and flowing too fast. Maybe we could have made it across, but it just felt much too risky. According to our guidebook and to the map, the glacier-fed river was supposed to spread out into a delta before joining the valley’s main river. Crossing the delta where the river is divided into many smaller streams was supposed to be no problem...but these days, the river doesn’t spread out—it stays in one wide, deep, rushing streambed that did not look at all safe to cross.

We followed the river several miles steeply upstream in hopes of finding a better place to cross. But the farther upstream we went, the more the river sank into a hopeless ravine. The higher we went, the more the sides of the ravine were lined with snow. Eventually, we were high enough that we used our snow shoes for long stretches. But as the sides of the ravine became steeper and steeper, our snow shoes were no longer enough protection. In order to continue upstream, we’d need ropes, harnesses, ice axes, and crampons—none of which we were carrying. There was nothing left to do but turn around and detour around the valley. In total, the journey in and out of Guohpervagge Valley cost us four days, one of which was spent in the tent waiting out relentless rain and fog.

After making our way into Sarek’s “main thoroughfare” of Ruohtesvagge Valley, we began to see people. We hadn’t seen a singe other person for five days, so it was a bit shocking to see other hikers, even more shocking to have to interact with them. It’s not hard to understand why Ruohtesvagge is so popular—not only is it the most direct route through the park, but the scenery is unbelievably dramatic. I have started calling it “The Valley of the Kings” because of the towering pyramidal mountains and hanging glaciers that line the valley.

We only spent a day in the main valley before turning off onto a side valley again. This time, we approached Guohpervagge Valley from the other side. We knew we’d have to turn around and walk back out the way we came, but we didn’t want to let that dangerous river keep us from experiencing the valley’s dramatic enclosure by high mountains. The weather cooperated with us and we had a beautiful couple of days in the valley and enjoyed the spectacular mountains, the herds of reindeer, the glaciers, and the river at the bottom of the valley. It was a relaxed and enchanted couple of days.

For the rest of the journey out toward Aktse cabin, we more or less followed the main route through the park. That didn’t mean that it was easy hiking—some sections were still trail-less and some sections were brutally difficult—but it did mean that we regularly saw a few people every day.

There was one day that I really did not enjoy, in fact the hiking conditions were hellish and I never want to go back to that area again. We spent almost the entire trip above treeline. Sometimes the terrain was tough with big, blocky stones that we had to negotiate a path through. Even more difficult were seas of loose, soccer ball sized stones. Sometimes the terrain was boggy and we had to tromp through the bog. But for the most part, above treeline, the terrain was fairly easy despite the lack of trails—grassy meadows covered in flowers or low heaths of flowering heather.